Continuums

Written by Gray Cook FMS Pod Casts

This past summer, I had an opportunity to work with Dan John. You should know, by now, that I’m a big fan of Dan’s work and unique perspective.

Dan is one of those coaches who tries things more than he talks about them. After he’s tried them and found value, he almost can’t stop talking about them. When Dan gets a question, he talks to a few people and gains perspective. Then he goes into the gym. He enters a training situation and a coaching mentality and recruits feedback from multiple people.

Only then can he determine how and what he thinks about an exercise.

Dan has always implemented certain principles in the way he develops someone and that is why I wanted Dan standing next to me when we approached The Essentials of Coaching and Training Functional Exercise Continuums. Last spring, I sat down with the FMS staff and we looked at ways to map out systematic thinking in the development of exercise continuums. People may think that we snap exercises together like puzzle pieces, but it doesn’t really go that way.

First, let’s make sure that we all have the same definition of a continuum: A continuous sequence in which adjacent elements are not particularly different from each other although the extremes are quite different.

When we introduce somebody to a series of exercises, hopefully we have a goal or a pinnacle exercise that demonstrates everything in fine working order. Once we know that end destination, it is our job to connect the exercise movements—from a very low level of complexity and competency all the way to the place that we want to go. But we need to snap those together in a sequence to ensure that the person performing the exercise will not have an unnecessary detour, all too often seen in current fitness development and athletic development.

My first order of business in avoiding that little hiccup or glitch is to develop a better forecast. When we just can’t get deadlifts going right, or can’t seem to get the sequence on a pull-up, or can’t do a kettlebell swing, we likely didn’t know our map well enough. Something occurred that we neither intended nor expected. We should have known the person a little bit better because a continuum is an environment that we create.

We step in—in place of nature, in place of the natural development that this person was going through—and we say, “We’re going to do this instead.” Returning to my recent articles on Physical Education, I’ll reiterate: I don’t think we can develop you better than nature. I think that some of the strongest, fastest and most skillful movers on the planet may have already lived out their lives, many of them without ever being coached.

I’m not going to assume for a minute that my small brain is wiser than the entire natural system that has developed us but I do feel comfortable in saying this: Even though I don’t believe I can develop you better than nature, I do think that I can do it quicker and I also feel like I can do it safer. Having said that, I feel comfortable piecing together an exercise continuum that will get you from Point A to Point B. I will base it on what I know about the activities and what I know about you.

While we understand the continuum—we get how one exercise seamlessly gives rise to the next more complex pattern—we don’t always understand the person we’re putting through it. That’s the biggest problem I see in continuums. If the person has fundamental mobility and stability issues, don’t be surprised later—get those off the table now.

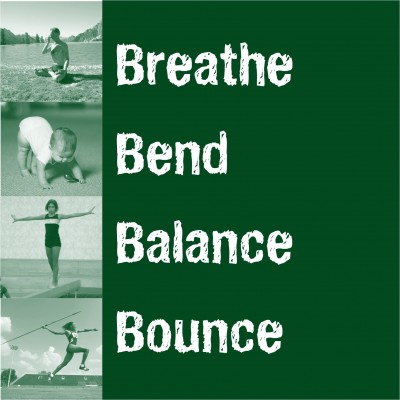

In our pre-conference workshop for Perform Better this year when Dan and I explored continuums, I discussed some movement behaviors that must be managed. I talked about breathing, bending, balancing and bouncing—The Four Bs.

Even though it sounds like I’m getting ready to tell a story with Winnie the Pooh in it, that’s not what I’m talking about at all. I need you to have a quick way to remember that each one of these abilities builds upon the other. If your breathing is not right, any martial artist or yoga practitioner from the last 4,000 years of history will tell you that you missed the starting point. If your breathing is not correct at rest or with escalated activity, everything else will be broken. It is the one rhythm that you cannot do without.

Breathing is the one attribute that functions both consciously and at an unconscious or subconscious level. At any time you can manage your state by controlling your breath. Are you angry or over-exerted? There are ways you can breathe to make that situation better. If you don’t know that or don’t understand that and are a fitness or rehabilitation professional, quickly explore breathing, observe its responses to the loads you place clients or patients and don’t immediately try to coach it.

Bending follows breathing and is your ability to yield to your environment and create sensory information. I am passionate about mobility—not for the biomechanical necessity, but for the sensory input. Why do I obsess on changing mobility before I approach stability? I consider most of your stabilization to be just like your breathing—performed at a subconscious or unconscious level. Your stabilization runs most of the time at a reflexive level. You’re not thinking about it—you balance effortlessly while focusing on another task.

If your mobility is compromised enough to make you compensate, the sensory input that you have to your reflexive behavior is askew—you have an overload of information or an underload of information. Either way, you’re not receiving the information you need.

We all understand the biomechanical reason for compensation. However, if your mobility is compromised, I can test your natural learning loop. If sensory information is not converted to perception and perception is not converted to action, you’re not going to get better without embracing the idea of changing mobility. Even if mobility never becomes normal, don’t let that be an excuse—try to improve it in an appreciable way prior to going into stabilization, which takes me to balance.

Balance is far more than your equilibrium or the ability to stand on one foot for 20 seconds. You use your balance in a deadlift. You use your balance in a Turkish Getup, in a Farmer’s Carry, when you swim. You use your balance in nearly all movement situations—first to keep you aligned and then to gauge the amount of muscle contribution between agonist and antagonist.

Lastly, we arrive at bounce—the way you use your backswing to pre-load your golf swing or cock your arm back before you punch. Bounce describes the stored energy when one foot hits the ground and you create your own reflexive situation along with the elastic component of your muscle and tendon working.

If you watch babies, they don’t really do a lot of lifting. They move right through their patterns. They pick up things and carry them. Before you know it, they’re bouncing all over the place, running and sprinting around and swinging and throwing things. Babies skip the strength phase, which should make us ask ourselves, “Why are we so enamored with the strength phase?”

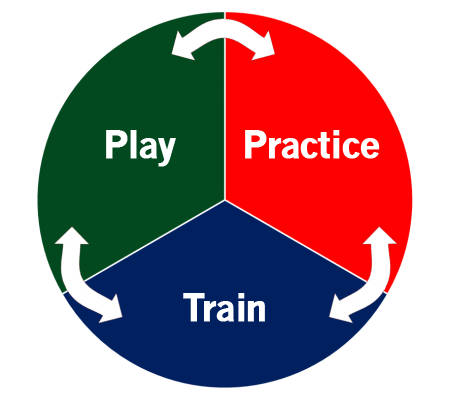

As Dan and I exposed the two continuums of the kettlebell swing or the push press, we thought:

What does it take to do a push press?

What does it take to do a push press?

You should probably have a good squat and a good press.

What does it take to do a kettlebell swing?

You should probably have a good deadlift.

We don’t see a lot of people with good kettlebell swings and we don’t see a lot of people with good push presses. If they do have a good push press, it’s likely a much better push press on their dominant side than their non-dominant side. There’s no reason for that asymmetry in a basic movement like a push press. We wouldn’t expect symmetry in a tennis serve or throwing a fastball, but if you can’t show me symmetry in a push press, something is wrong with your engine.

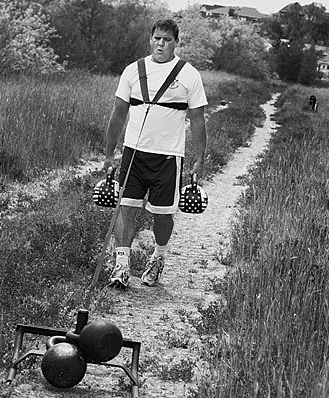

The moral of the story: Dan and I used both of these continuums to demonstrate that the lacking piece within most continuums is the carry phase. That is the number one reason why I wanted a coach of Dan John’s accomplishments and wisdom standing next to me. Dan has always had some type of carry as part of his personal development program and the development program that he does for others. Dan is the messenger for loaded carries.

I’ve tried to demonstrate how his wisdom actually works. Toddlers don’t do a lot of lifting but the things they do lift, they carry for a long time. When you carry, you must demonstrate alignment with integrity under load and this is reflex stabilization. If your carries are poor, if you dump your posture before you finish your task, we’ve demonstrated that the endurance of your stabilizers will not withstand power work because your prime movers do not really care if your stabilizers smoke out early or not. You will always squeeze out more repetitions. They just won’t be repetitions with integrity.

Therefore, we use carries (whether they’re a conventional Farmer’s Carry or a unilateral overhead to front rack to suitcase carry) to demonstrate your alignment with integrity under load and even your symmetry. If we can use your holds and carries to create integrity and alignment under load, then we’ve demonstrated that your stabilizers have the endurance, the feedback and the control to allow you to march along this power continuum without any unnecessary setbacks.

Most people go from patterning to lifting. They’re missing a step. By definition, the steps of a continuum should be almost unperceivable. They should meld together.Going from a pattern to a loaded pattern is not a continuum. Gain the pattern. Gain the alignment. Gain the integrity. Show me that you can carry things in different positions. When you can carry those things in different positions, I think you can lift with much better integrity, develop your strength authentically and move right into power without a hiccup.

In The Essentials of Coaching and Training Functional Exercise Continuums, we broke down the continuum to show you that the missing link in most continuums is a lack of a carry phase, a lack of a holding phase and the lack of alignment with integrity under load in very simple patterns demonstrating work capacity. I choose the words work capacity over strength because you can consider yourself strong with a 1-RM but I may not want you backing me up climbing a mountain. I want someone with work capacity.

We lift and we train to have enough work capacity to pursue the skills that we desire to develop. If your work capacity is lacking, most of your skills will be practicedwithout integrity and alignment under load.

You need to know about continuums.

Related Resources

-

Saturate, Incubate, Illuminate

Posted by Gray Cook

-

Pandora and Exercise

Posted by Gray Cook