Addition by Subtraction

Posted by Dr. Lee Burton

At Functional Movement Systems, we’re known for screening, testing, and assessing. One of the main reasons to implement these procedures is to identify someone’s physical capabilities - what they can or cannot do from a movement perspective. We are not looking for movement perfection but for information to make educated decisions for the people in our care. Using this systematic process, we may uncover movement limitations. Limitations in range of motion (ROM) and/or motor control can lead to dysfunction, pain, or, even worse, disability over time. As professionals in the health and wellness community, we do our best to minimize, improve or eliminate these limitations and promote an overall improved state of being for the people we serve in our respective disciplines. That state of being can mean different things for different people. Identifying and understanding these limitations can help direct our interventions to ensure we are working toward improvement and not creating further dysfunction!

At Functional Movement Systems, we’re known for screening, testing, and assessing. One of the main reasons to implement these procedures is to identify someone’s physical capabilities - what they can or cannot do from a movement perspective. We are not looking for movement perfection but for information to make educated decisions for the people in our care. Using this systematic process, we may uncover movement limitations. Limitations in range of motion (ROM) and/or motor control can lead to dysfunction, pain, or, even worse, disability over time. As professionals in the health and wellness community, we do our best to minimize, improve or eliminate these limitations and promote an overall improved state of being for the people we serve in our respective disciplines. That state of being can mean different things for different people. Identifying and understanding these limitations can help direct our interventions to ensure we are working toward improvement and not creating further dysfunction!

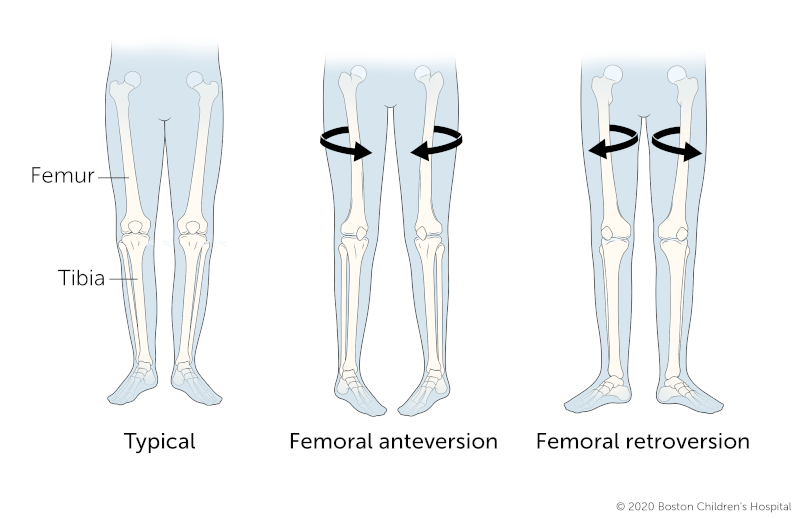

Femoral neck anteversion is the angle between the femoral neck and femoral shaft, indicating the degree of torsion of the femur1. Multiple publications describe the etiology, epidemiology, causalgia, diagnostic imaging, physics/biomechanics, muscle activation implications, and possible musculoskeletal health consequences of anteversion and retroversion. They are beyond the scope of this article and can be further researched at a different time. To keep this very simple, anteversion is a directional rotation/torsion of the femur that affects the biomechanics of the hip. “Ante”2, as a medical prefix meaning toward the front, describes the abnormal rotation of the femur inward.

Conversely, “retro”2, the medical prefix meaning back, describes the abnormal rotation of the femur outward. This abnormal torsion of the femur can cause a host of issues upstream and downstream, affecting things like foot positioning, tibial torsion, delays in or difficulty walking, poor coordination, hip/knee osteoarthritis, low back pain, and disrupted functional patterning. If not correctly identified, functional patterns of rotation, squatting, and hinging(deadlifting) can be greatly affected by the torsional changes seen in the femur. The negative effects can be amplified if these patterns are performed or trained with velocity or under load. That’s inversely related to our goals of promoting an improved state of being!

So, how do we identify this torsion of the femur? To identify this structural change, we must go back to the concepts of screening, testing, and assessing. We can start by visually looking at the standing posture of the individual before us. We may see more of a toe-in or “pigeon-toed” presentation with femoral anteversion. Conversely, we may see a more toe-out or “duck foot” presentation with a retroversion torsion.

This observation alone may clue us in that further testing may be appropriate. Just be sure to note that toe-in or toe-out positioning does not necessarily mean there is a torsion of the femur. It simply may be an indicator that this structural change may be present.

In the Functional Movement Screen (FMS), one might present with a 0 or 1 in the overhead deep squat. A score of 0 would indicate pain is present, prompting further local assessment by a medical professional, as discussed in the Selective Functional Movement Assessment (SFMA). A score of 1 would mean the pattern cannot be completed per the defined criteria. You may also see a score of 0 or 1’s with hurdle step (HS) or in-line lunge (ILL). This is because the static stability and dynamic components of the patterns may be compromised by the rotational torsion in the femur and limit the mobility or stability required to complete the patterns.

In the SFMA, we may see dysfunctional non-painful (DN) or dysfunctional painful (DP) patterns of multi-segmental rotation (MSR), single leg stance (SLS) or arms down deep squat (ADDS). In the SFMA, when we dive deeper into assessment during the breakouts, and would likely see a large rotational ROM swing in one direction versus another. These swings in rotational ROM can be seen prone in the MSR breakout or seated, with the hips flexed, in the ADDS breakout.

For example, when we assess hip rotation in the prone position, we expect to see about 40 degrees of hip external rotation and 30 degrees of hip internal rotation. In this example, we can visually see a large rotational ROM swing - limited hip external rotation but increased hip internal rotation.

Once alerted to these positional or movement indicators, we can then perform a common yet underutilized orthopedic test to attempt to functionally determine if anteversion or retroversion is present. Enter Craig’s test. Craig’s Test (Trochanteric Prominence Angle Test) can easily be performed without costly imaging and can help assess femoral/hip anatomy.

To perform Craig’s Test, follow these steps:

The normal angle of torsion should fall between a window of 8-15 degrees of internal rotation (tibia shaft away from the midline).

If the angle is greater than 15, there is a high probability that the femur is anteverted. Less than 8 degrees or closer to perpendicular, the probability of retroversion exists. It’s also beneficial to state that no “perfect” orthopedic tests exist. Nothing compares to the accuracy of diagnostic imagining. Still, Craig’s Test is a readily available, no-cost option that can help us understand some of the how's and why’s in the clinical and physical presentation of the person in front of us. This paper by Souza and Powers3 describes some of the highly correlated inter and intra-rater reliability of Craig’s Test but shows some disparity against MRI. As is usually the case, other studies like the one by Rue et al. 4 show the reliability of clinical testing versus X-ray. Not everyone “needs” imaging but be sure to follow best practices when identifying this structural change, especially where pain and loss of function are involved.

Now that we’re armed with some indicators that may cue us into identifying the presence of femoral torsion, the question becomes what we do about it. Keep in mind that femoral torsion, either anteversion or retroversion is a bony, structural deformity. This is NOT something we can change with manual therapy or exercise. We need to synthesize all aspects of the individual's presentation to truly find the optimal interventions. However, there are some things to avoid and some pathways to explore that are more likely to provide positive outcomes no matter what your respective discipline. We’re all in this together!

With anteversion, please do NOT stretch into external rotation. These individuals are NOT “tight.” There is a structural change to the anatomy which is limiting a ROM. Yes, the ROM may be limited, but that doesn’t necessitate stretching. This is why screening, testing, and assessing are vital to us. If these anteverted individuals are stretched into external rotation, they are placed in a position that impinges the bony anatomy of their hip. This impinged position can lead to the production/progression of pain, which we classify more globally as femoral acetabular impingement (FAI). If not managed correctly, FAI can lead to pain, dysfunction, and even disability over the long term.

Instead, let’s think of possible solutions for those with anteversion:

Remember the predisposition in an individual with anteversion; adding quad dominance to the equation can increase the alignment discrepancies, possibly introducing positions to the system that may increase injury-inducing mechanics. Posterior chain pattern retraining leading to posterior chain training may help reduce those positional risks. Think proper patterning in the hip bridge, progressively building up to rack pulls, deadlifts, and kettlebell swings as a framework. The framework concept is the same for bilateral or unilateral presentations.

In the case of a retroverted presentation, some different interventional strategies are required. Remember, these individuals will present with limited hip internal rotation and an increased hip external rotation range. Some solutions for those with retroversion might include:

Please note that these suggestions, modifications, and programming considerations may not always work 100% of the time for every individual. This brings us back to the concept of screening, testing, and assessing so we can thoughtfully tailor our interventions to the individual.

As health and fitness professionals, the more knowledge of the body system(s) we are trying to influence helps drive our decision-making process toward goals of improvement. Screening, testing, and assessing the musculoskeletal system increases our information and drives our interventional choices. Proper and well-thought-out choices make for robust programming in either the clinic/rehabilitation or performance realm. These choices usually lead to eliminating pain, and improved mobility, strength increase, durability, and performance longevity. Hopefully, this article acts as a refresher for some and as insight for others bringing to light the presence of the structural anomalies of femoral anteversion and retroversion. Proper identification and intervention will help lead to our goal of improvement for the individuals and community we serve!

References:

1. Femoral anteversion: significance and measurement

Matteo Scorcelletti, Neil D. Reeves, Jörn Rittweger, Alex Ireland

First published: 24 June 202

2. Merriam-Webster Medical Dictionary

https://www.merriam-webster.com › medical

3. Souza RB, Powers CM. Concurrent criterion-related validity and reliability of a clinical test to measure femoral anteversion. Journal of orthopaedic & sports physical therapy. 2009 Aug;39(8):586-92.

4. Clinical determination of femoral anteversion. A comparison with established techniques. Ruwe PA1, Gage JR, Ozonoff MB, DeLuca PA. The Journal of Bone and Joint surgery. American Volume, 01 Jul 1992, 74(6):820-830

PMID: 1634572

Posted by Dr. Lee Burton