Youth Soccer Injures and The 3 R's: Risk Assessment, Rehabilitation, and Reduction

Posted by Brad Papson

FAQs – frequently asked questions. Likely one of the FAQs we see most is the question of how we reconcile the idea of proximal stability for distal mobility with the FMS emphasis on mobility first?

Proximal stability for distal mobility is a concept that has been referred to by Moreside and McGill in their article on hip joint ROM improvements and in their research the “proximal stiffness training” did lead to improvements in hip range of motion(1). And Kibler noted that in reference to the concept of core stability: “Core muscle activity is best understood as the pre-programmed integration of local, single-joint muscles and multi-joint muscles to provide stability and produce motion. This results in proximal stability for distal mobility, a proximal to distal patterning of generation of force, and the creation of interactive moments that move and protect distal joints.” (2) The origin of the concept of proximal stability for distal mobility is often attributed to PNF (proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation developed by Kabat and Knott in the late 1940’s) and does appear in reference to evaluating and treating the trunk stating that “in an efficient state the trunk provides appropriate proximal stability or controlled mobility to support optimal task or postural performance.”(3) But please note the addition of controlled mobility.

The FMS is seven movement patterns used to set a baseline for fundamental movement competency. The patterns look at mobility, stability and functional aspects of fundamental movement. Once the screen is performed there is a corrective algorithm or hierarchy in the FMS that places priority on the mobility patterns first. Mobility patterns are prioritized because limitations in mobility can reduce and change proprioceptive input. According to Luis Mesquita: “…mobility is so important to perception. If mobility is reduced, afferent information from the proprioceptors is likely to be negatively affected, resulting in less awareness.”(4)

And this is where the confusion starts…

The interpretation of the “proximal stability for distal mobility” can lead to a reductionist conclusion that stability should be first and sometimes “only." The interpretation of the FMS corrective hierarchy can lead to a reductionist conclusion that mobility should be first or isolated. However; the concept of proximal stability for distal mobility does not imply isolated stability or stability first. And the FMS corrective algorithm prioritizes the mobility patterns (ASLR and SM) but does not say mobility only or mean to imply it’s in the absence of stability. FMS is looking at patterns of movement that include both “mobility and stability” within the whole pattern.

In the ASLR pattern for example; while referred to as a mobility pattern (and sometimes misinterpreted as a “hamstring test”) there is a pattern being looked at that includes lumbopelvic control, posterior chain and anterior chain activation that coordinates flexion on one side in the presence of extension on the opposite side. So in the ASLR; we could end up beginning with addressing issues within the pattern via lumbopelvic control (stability), posterior chain restriction or anterior chain restriction. And that would just begin the process of working on and within the pattern since changing the ASLR involves re-patterning the leg raise into activities like a good single leg deadlift etc… So the key to addressing a restricted ASLR could mean improving the lumbopelvic control via “core activation” or “stability drills” or it could mean that traditional stretching drills will be needed so we “crack” the mobility increasing range of motion and perception a bit before the “motor control drills” will be effective. Every individual is different and why their body decided to compensate within that pattern and the “code” to improve that pattern will be unique to them. Using the baseline of the FMS you have a tool that will allow you to know you are headed in the right direction. Improvements happen or they don’t and you will know because the baseline gives you feedback.

The Shoulder Mobility screen is similar in that we are looking at a pattern that involves good thoracic spine mobility and control, scapular control, glenohumeral range of motion and control in a reciprocal reaching pattern with the upper limbs. While “stability” and control of the scapula can be a key, that “stability” and control is interdependent on the thoracic spine. Again the individual will hold the key and it may be “proximal stability” or it may be “mobility” that cracks the code on improving the pattern. The baseline will guide you.

So, FMS fully recognizes the concept of proximal stability for distal mobility and the idea that mobility is important for good proprioception and patterning. The solution for a movement pattern can absolutely be driving proximal stability but that proximal stability can be within a mobility “biased” pattern.

As the corrective strategies progress, FMS further drives proximal stability via irradiation in the Chop and Lift. “These movements capitalize on the principles of proximal to distal and distal to proximal overflow (also known in the PNF literature as irradiation)(1). According to Knott and Voss, distal to proximal sequencing is essential to improve of motor abilities. Reinforcement of the movements by addition of resistance may strengthen the response in a weaker portion of the pattern. Coordinated movements of multiple muscles acting in a kinetic sequence helps to provide sequential, fine-tuned muscular actions.” (4)

The Chop and Lift are used in tall kneeling, half kneeling and standing positions/postures. Tall and Half kneeling are used because: “The tall and half kneeling postures are developmental steps on the ladder of function. These two lower body postures are familiar to rehabilitation providers who practice neuro-developmental strategies during treatment of patients whose central nervous system function is compromised. Earliest or lowest developmental postures include bridging, quadruped, planking, and rolling. The highest level developmental posture is standing (“floor based” upright postures) or other functional postures which offer challenges to multiple systems (neuromuscular, proprioceptive/ coordination, vestibular, etc.) with little external input. The authors of this article prefer the term “transitional postures” to describe the two kneeling postures. These transitional postures will be emphasized due to their ability to stress or recruit the smaller stabilizing muscles of the core.” (4)

The Chop and Lift are used in tall kneeling, half kneeling and standing positions/postures. Tall and Half kneeling are used because: “The tall and half kneeling postures are developmental steps on the ladder of function. These two lower body postures are familiar to rehabilitation providers who practice neuro-developmental strategies during treatment of patients whose central nervous system function is compromised. Earliest or lowest developmental postures include bridging, quadruped, planking, and rolling. The highest level developmental posture is standing (“floor based” upright postures) or other functional postures which offer challenges to multiple systems (neuromuscular, proprioceptive/ coordination, vestibular, etc.) with little external input. The authors of this article prefer the term “transitional postures” to describe the two kneeling postures. These transitional postures will be emphasized due to their ability to stress or recruit the smaller stabilizing muscles of the core.” (4)

In a study on Irradiation it is stated that: “The trunk is the central region for motor control of lower and upper limbs and can irradiate to them. …this motor control can be disturbed and does not allow effective movements at limbs. (6)” “This principle (Irradiation) is based on fact that stimulation of strong and preserved muscle groups produces strong activation of injured and weak muscles, facilitating muscle contraction. So, these weak muscles can develop an increase in the duration and/or intensity by the spread of the response to stimulation…” (6)

In a study on Irradiation it is stated that: “The trunk is the central region for motor control of lower and upper limbs and can irradiate to them. …this motor control can be disturbed and does not allow effective movements at limbs. (6)” “This principle (Irradiation) is based on fact that stimulation of strong and preserved muscle groups produces strong activation of injured and weak muscles, facilitating muscle contraction. So, these weak muscles can develop an increase in the duration and/or intensity by the spread of the response to stimulation…” (6)

And this really ties the concept of proximal stability for distal mobility and the use of the chop and lift together. Using the upper limbs to drive an overflow of activation from distal to proximal or proximal to distal muscle activity to enhance the pattern of motor control for the trunk.

What appears to conflict in the beginning really has no conflict at all. Especially when a pattern based approach is used. Proximal stability may very well drive distal mobility in a particular pattern even if that pattern has a mobility bias. And remember the PNF reference to “proximal stability or controlled mobility to support optimal task or postural performance” where we are reminded of the efficient interplay of “stability and mobility” to create efficient movement.

References:

Chapter 11 page 259

Brett Jones is StrongFirst’s Chief SFG Instructor and an Advisory Board Member with Functional Movement Systems. He is also a Certified Athletic Trainer and Strength and Conditioning Specialist based in Pittsburgh, PA. Mr. Jones holds a Bachelor of Science in Sports Medicine from High Point University, a Master of Science in Rehabilitative Sciences from Clarion University of Pennsylvania, and is a Certified Strength & Conditioning Specialist (CSCS) from the National Strength and Conditioning Association (NSCA).

With over twenty years of experience, Brett has been sought out to consult with professional teams and athletes, as well as present throughout the United States and internationally.

As an athletic trainer who has transitioned into the fitness industry, Brett has taught kettlebell techniques and principles since 2003. He has taught for Functional Movement Systems (FMS) since 2006, and has created multiple DVDs and manuals with world-renowned physical therapist Gray Cook, including the widely-praised “Secrets of…” series.

Brett continues to evolve his approach to training and teaching, and is passionate about improving the quality of education for the fitness industry. He is available for consultations and distance coaching by e-mailing him at appliedstrength@gmail.com.

Follow him on Twitter at @BrettEJones.

Posted by Gray Cook

Awesome article! Keep them coming!

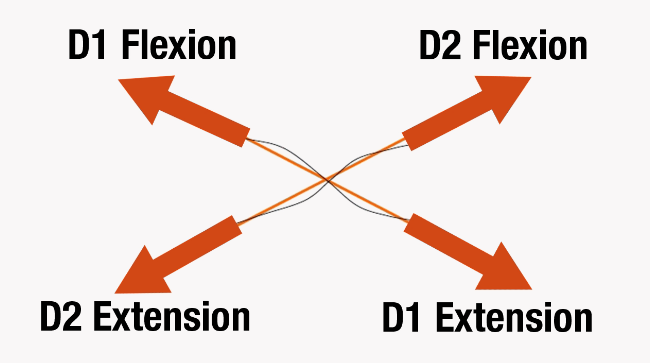

Excellent clarification of how to effectively use the FMS. In the Irradiation study of D1 Flexion & D1 Extension & D2 Flexion & D2 Extension are they referring to the anterior & posterior oblique system? In a previous article Gray Cook talked about the coloration of the ASLR & the Shoulder Mobility screen to check the breathing pattern. I created a form for that. With the Proximal Stability for Distal Mobility is that also a factor evaluated in the screening? Thanks.

Yes, please keep them coming.