Using the FMS to Manage the Injury Risk of 19,000 First Responders

According to

data compiled by EHS Today, workplace injuries that caused employees to miss six or more days of work cost US companies over $62 billion (total cost of all injuries and illnesses exceeded $250 billion). What’s especially notable is that one-third of injuries which resulted in SIX days or more of missed work were repetitive or overuse in nature. For everything that organizations do to minimize expenses, maybe we’re missing a massive opportunity in taking care of our most important assets: our people.

We wanted to feature a friend and tremendous ambassador of FMS has made an exceptional commitment to the health and movement of his team. Mick Stierli is a Sergeant with the New South Wales Police Force based in Sydney, Australia where he is the Health and Fitness officer, Physical Training Instructor’s Coordinator as well as a Weapons and Defensive Tactics Instructor. In addition to being a respected officer, Stierli is largely responsible for creating one of the most comprehensive physical training programs ever implemented in a tactical workforce. The program is rooted in using the FMS to evaluate the movement capabilities of 19,000 officers who are spread across a geographic area larger than the state of Texas. It was a tremendous undertaking with benefits that extend far beyond the physical health of the officers.

Of the need to develop a strength and conditioning program and incorporate the FMS, Stierli said: “In the police force we have daily checklists: we check our vehicles, our weapons, but we never checked our people. I think our people are our most important assets.”

Stierli’s motivation isn’t limited to his police force, either. His goal to share their experience as broadly as possible. As such, he has published a wealth of information on his findings, recognizing the disparity in research between training athletes and training a tactical officer.

"If you wanted to look up how to train a volleyball player or baseball player, you can easily find that. Our goal is to share how to share how to train a police force."

The hard cost of injuries is indisputable. Regardless of the occupation, missed time is one of the most significant expenses an organization can incur. One of the most convincing papers was presented by Michael Contreras of the Orange County Fire Authority at the 2013 Functional Movement Summit. Here are a few of the findings:

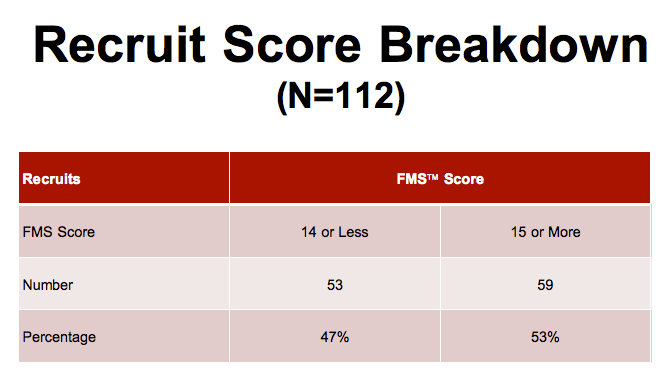

Results from screens of 112 OCFA firefighters found over half (53%) scored a 15 or higher on the FMS. It’s important to note that these statistics are based on total sum scores. While a number of studies have shown a relationship between an increase in injuries and a total score of less than 14, we prefer to assess data sets on a test by test basis. A score of a 14 isn’t necessarily all 2’s, but can be made up of dangerous 1 and 3 asymmetries.

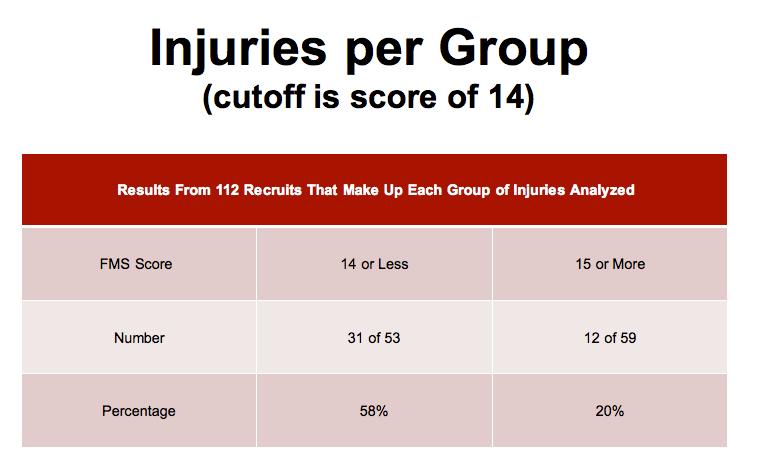

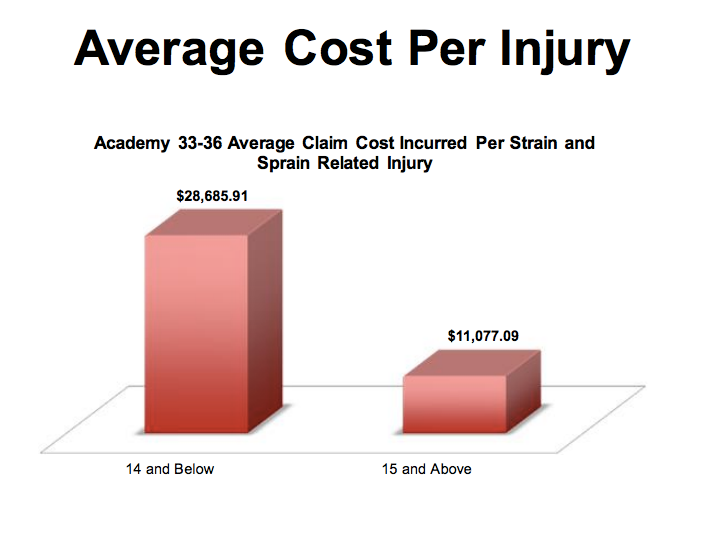

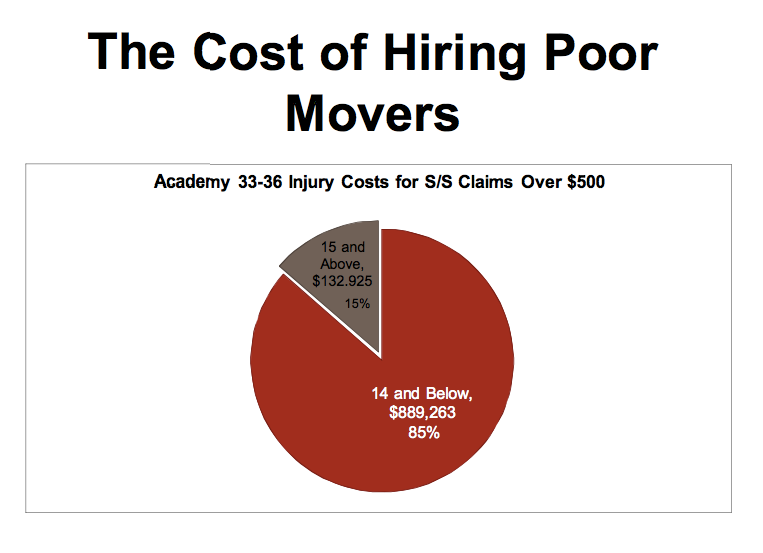

The results of this particular population group suggest a relationship between total FMS score and injury rate. 47% of the firefighters accounted for 72% of the injuries. And expensive injuries at that.

The numbers are definitive. Injuries are wildly expensive. Additionally, many of the injuries are not what you would expect from a particular line of work.

According to data from a

2005 study published in Anesthesia and Analgesia, musculoskeletal injuries in the military often account for more injuries than actual combat. This trend isn’t limited to the military, but extends to other tactical workforces.

Via PT on the Net:

For firefighters, musculoskeletal injuries has been attributed to being a leading cause of compensation and injury reporting, even overshadowing actual burns (Karter, Molis, & Association, 2011; Walton, Conrad, Furner, & Samo, 2003). In police, apart from direct physical assault from offenders, injuries are commonly caused by the handling of non-cooperative offenders to more mundane factors like the interaction between hip holster and police car seats with the officer required to rotate to either exit the vehicle (sometimes at speed) or read from their mobile data terminal (Orr, 2013a).

Additionally, the benefits of improving the physical health of your workforce may extend beyond how well they move. A 2013 study co-authored by Stierli found that a return to work conditioning program actually improved the attitude and mental health of personnel within the organization.

“We didn’t implement the FMS for the sake of testing, but for the sake of changing our culture in how we take care of our most important assets.”

The results of Mick Stierli’s work have been exceptional, but they haven’t been easy, nor is the process complete. “It takes 10 years to change a culture,” said Stierli, “We’re probably five years in.”

“We don’t use the FMS as a tool to evaluate how well you do your job, but we hope it helps you live well.”

“It does take time,” said Stierli, “A lot of people would say “we don’t have time to roll it out.” If we can incorporate the FMS in a station of 19,000 officers, anyone can do it.”