Group Exercise and the FMS

Posted by Brett Jones

This review was originally posted by Tony Gentilecore on his website/blog. Here's a little more about Tony in his own words.

Tony Gentilcore is one of the co-founders of Cressey Sports Performance, which really should have been called "Cressilcore Sports Performance" because that sounds like an awesome castle where a wizard lives (and plays sports).

When he’s not picking things up and putting them down, he trains top-level athletes, contributes to the top fitness magazines and websites around, and sets up a camera in his garage to record his lightsaber skills.

Now, here's what Tony had to say after recently taking the FMS Level 1 & 2 courses.

This is what I looked like last Sunday after spending three days and 20 course hours taking the Functional Movement Screen Levels 1 & 2.

That’s my face melting.

It sounds (and looks) like a bad thing, but I assure you it’s the exact opposite.

Sitting through 20 hours of anything can be daunting.

Sitting through 20 hours of non-stop talk on anatomy, assessment, corrective exercise, and how much I suck at the Active Straight Leg Raise can be downright overwhelming. And to be honest there were times I was overwhelmed.

But this was easily one of the best 20 hours I’ve spent doing anything not involving a book, baseball, Star Wars, or chocolate covered strawberries. BOM CHICKA BOM BOM.

But this was easily one of the best 20 hours I’ve spent doing anything not involving a book, baseball, Star Wars, or chocolate covered strawberries. BOM CHICKA BOM BOM.

Trying to overview the entire experience in one simple blog post isn’t doing it any justice. But I figured I’d try to highlight some “big rock” concepts and tidbits of information I learned while everything was still fresh in my head.

Lets Do This

I’d be remiss not to first give a shout out to both Functional Movement Systems and Perform Better for putting on and running a class-act event. The two together are like peanut butter and jelly or Jordan and Pippen or Batman and Robin.

I’d also be remiss not to lend a huge kudos to the bandleader, Brett Jones, who was the epitome of class and professionalism the entire weekend. He’s like Justin Timberlake, only with kettlebells. And a 500+ lb deadlift.

I’d also be remiss not to lend a huge kudos to the bandleader, Brett Jones, who was the epitome of class and professionalism the entire weekend. He’s like Justin Timberlake, only with kettlebells. And a 500+ lb deadlift.

He along with Mike Perry and Diane Vives did an amazing job coaching all the attendees up and offering their expertise. A slow clap goes out to all of them.

NOTE: From here on out I’m using bullet point format because what follows is going to be a massive brain dump that may or may not make any sense. Good luck.

– The “S” is the most important letter in “FMS.” It’s a (S)creen. Nothing more, nothing less. It’s NOT an end-all-be-all assessment. I’ve always used components of the FMS when assessing my athletes and clients, but always viewed it as the outer layer of an onion. If I need to peel back more layers and dig deeper with other protocols I will.

What does the FMS accomplish? In a nutshell: it ascertains whether or not someone can “access” a pattern.

- Simplifying things even more: the FMS helps to figure out if “you move well enough to do stuff.”

– The FMS can also be seen as a litmus test to see if someone is at risk for injury. Of course a previous injury is going to be the greatest risk factor, but the FMS looks at other things such as asymmetries, mobility, stability, and neuromuscular control.

A great analogy that Brett used to describe the process was to ask the audience whether or not smoking increases the risk of cancer? Yes. Does not smoking protect you from cancer? [Interesting question, right?]

Just because you do or do not do something doesn’t mean anything. The primary goal(s) of the FMS is to set a movement baseline, identify the pain or dysfunction, and set up proper progressions and conditioning to address it.

– Fitness professionals are the worst at testing. We overthink things. There’s no such thing as a “soft” or “hard” 2. There’s no such thing as a 1+ or 1-. The screen is the screen, and it’s important (nay, crucial) to hold yourself to the standards and criteria set forth by the manual.

I’m paraphrasing here, but it either looks good – and meets the criteria for testing – or it doesn’t.

You can’t overthink things or start doing stuff like, “well, his heel only came up a teeny tiny bit, and only rotated 8.3 degrees. I guess that’s a 3.”

– We can’t feel bad for giving people the score they present with and deserve. It’s doing them a disservice in the long run. It’s just like Brett said and made us pledge as a group before we started testing one another: “I’m still a good person and am not a failure if I score a 1.”

It’s not the end of the world and you won’t be considered the spawn of Satan if scored a “1” on your Deep Squat screen.

Life…will…go…on.

Seriously, refer out.

But that doesn’t mean we still can’t train the athlete or client. As coaches we can usually train around any injury; we don’t need to keep everyone in a safe bubble where we just tell them to “rest.” To me that’s unacceptable and not an option.

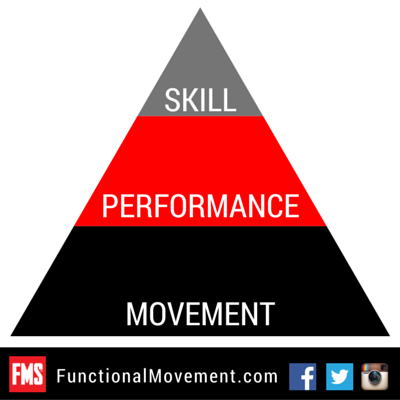

– Take a gander at the Functional Performance Pyramid. Don’t worry I’ll wait.

If you decrease one’s movement capacity and increase their performance (make the movement block less wide compared to the performance block), that’s bad.

If you increase one’s movement capacity (think: yoga) and decrease their performance, that’s also bad.

We’re really good as coaches and personal trainers at building better engines (improving performance), but neglect to address the brakes and suspension (movement). Hence, people often break down sooner.

This is also another fantastic reason why the FMS is valuable. It’s helps you figure out where people need the most work/attention.

– Raise your hand if you feel the Active Straight Leg Raise is a great screen to test for hamstring length.

It’s not.

If anything it’s more of a screen for the “core,” and how well you’re able to control your pelvis. I.e., can you maintain extension on the down leg as you bring the other into hip flexion (and vice versa).

– The Deep Squat Screen (<—- bolded on purpose) takes place with the toes pointing straight a head. It’s not how we coach the squat in the long run.

[Related: Squat Movement vs. Squat Exercise. What's the Difference?]

1. Toes forward provides some semblance of standardization. It doesn’t make sense to allow people to externally rotate their feet (even a little bit) because that defeats the purpose. You allow someone to rotate 5 degrees, and the next person rotates 15.

2. Toes forward also makes it easier to see faults and compensations in the pattern.

[Related: The Most Common FMS Squat Question]

I literally had a “tense” exchange with another attendee who gave me push back on making them perform the screen with toes pointing forward.

Fellow Attendee: “Well I can’t squat if they’re forward!”

Me: “Then you won’t get a 3.”

Fellow Attendee: “But I was told we could point our toes out."

[Relax, deep breaths]

Me: “Sorry but we were told otherwise yesterday. Toes forward.”

With a little bit of a huffy attitude my fellow attendee reluctantly conceded and ended up with a 2.

– Corrective exercise is like boxing. It’s generally accepted that there are four different kinds of punches in boxing: the jab, cross, hook, and uppercut. The Five-Point-Palm-Exploding-Heart-Technique from Kill Bill didn’t make the cut.

– Breathing is all the rage in fitness today. And for good reason: it’s something that needs to be addressed.

I’ve seen magical things happen when you help someone address a faulty breathing pattern. But piggy-backing off the previous comment about corrective exercise, you don’t need to get all fancy pants on people.

Showing your athletes and clients how to properly perform “crocodile breathing,” where they learn to get 360 degree expansion (and to not rely on their accessory muscles like the upper traps, scalenes, etc) can go a long ways in helping to set the tone on fixing stuff….even a straight leg raise or shoulder mobility.

Dumbledore can’t even do that.

How’s that for a super scientific explanation.

– You need to be RELAXED when you foam roll. We’re not deadifting max effort weight here. Chill out.

– Don’t underestimate the power of grip work (squeezing the handle of a dumbbell or kettlebell) to help improve rotator cuff function as well as shoulder mobility.

– You need a minimum of 30 degrees of ankle dorsiflexion to run well. Just sayin…..

– Here’s one of the best analogies I’ve ever heard with regards to overhead pressing courtesy of Brett Jones. When explaining the path of the DB or KB during an overhead press tell your client to pretend as if there’s a booster rocket underneath the elbow and that it takes the weight to space.

The path should be straight up, not to the side or in a zig-zag fashion. Straight up.

I Could Easily Keep Going

But I think that’s enough.

Needless to say I HIGHLY encourage any and all fitness professionals to attend one (or both!) of these courses if you have the opportunity to do so. I learned a ton and there’s no reason to suspect you wouldn’t either.

Interested in learning more?

Posted by Brett Jones

Posted by Gray Cook

Posted by Greg Dea