Walk the Line

Written by Gray Cook FMS

Since the Exploring Functional Movement: (DVD), (Digital) project I did with Erwan Le Corre of MovNat, balance has been a major topic at my Perform Better Summit appearances, where I have about an hour to help people learn to balance better. In the hands-on workshop, people walk a balance beam, then get to a hurdle-like obstacle and have to step over it. We see a lot of faltering early in the session.

Balance and stability are an integral part of almost every sport or activity. A concept I use to describe stability is ‘motor control,’ which might better define the subtle adjustments we make with the stabilizer muscle groups while the larger muscle groups propel us forward, turn us, or slow us down. That stability can easily be analyzed or even trained in a balance situation.

Balance and stability are an integral part of almost every sport or activity. A concept I use to describe stability is ‘motor control,’ which might better define the subtle adjustments we make with the stabilizer muscle groups while the larger muscle groups propel us forward, turn us, or slow us down. That stability can easily be analyzed or even trained in a balance situation.

One of the mistakes we make in training is to go right into training single-leg stance. Single-leg stance is a great test for balance; you see it in the Functional Movement Screen with a hurdle step, and you see it in the SFMA with a single-leg stance test.

We have many variations, and we always compare the left and the right sides. We look at single-leg stance with eyes open and eyes closed. There are different ways to break down single-leg stance, but when it comes time to train, it’s sometimes better to give the brain a little more meaning.

In the Exploring Functional Movement video, we found all kinds of opportunities to get on a beam or a pole or to balance on a line. That’s where the title Walk the Line comes from.

Instead of putting clients in a doorway to challenge single-leg stance, a beam provides purpose—single-leg stance, one side, the other side, and then walk the beam. When we do things to juice balance, people can walk up and down a beam, and can practice that.

In our physical therapy clinic, we work with different levels of balance. We have a piece of Trex board, which is synthetic decking we ripped down to a four-inch ‘beam,’ although some people feel more comfortable starting with a six-inch width.

Beam walking is something we superset in fitness, say after a hard set that makes you tired. You’re going to need a rest break before the next set of walking lunges, front squats or kettlebell swings. Why not walk a beam while you’re recovering? It’s sensory motor engagement. It’s not high demand, but it does require a stabilizer reset, and doing that may actually make the next set of lunges, squats or swings tighten up a little.

Beam walking is something we superset in fitness, say after a hard set that makes you tired. You’re going to need a rest break before the next set of walking lunges, front squats or kettlebell swings. Why not walk a beam while you’re recovering? It’s sensory motor engagement. It’s not high demand, but it does require a stabilizer reset, and doing that may actually make the next set of lunges, squats or swings tighten up a little.

Walking that beam barefoot or in minimalist footwear, whether the ‘beam’ is elevated off the ground or flat on the ground, is a self-limiting activity because it provides quick feedback. But I don’t like to see intense concentration. I don’t like to see you looking at your feet; I don’t want to see you flailing your hands.

At the recent CK-FMS, I coached people through a little gauntlet of balance beams. We use it in the rehab setting at the clinic, all the way to a fitness setting like CK-FMS, and it doesn’t have to be an exercise of itself. It can be a superset to complement another exercise. Here, have a look.

When trying to improve balance, the first pre-requisite is to check for mobility. If you can’t pass the hurdle step test, we may want to grab some mobility before we challenge balance. If you have restricted ankle dorsiflexion, your hips are extremely stiff, you can’t touch your toes, or you can’t even break parallel on a deep squat, you may be running up against a mobility problem that’s hurting the sensory feedback of the balancing activity. You’re going to balance better if we get you a little more mobile before the next balance challenge.

If your FMS score has a bunch of ‘2s,’ and you don’t have a lot of flexibility problems, you could probably get after some pretty good balance challenges to feed the system. You have enough sensory information coming in to probably get better motor control, and then you can refine it.

Listen carefully to what I said. If you have ‘1s’ on the movement screen, attack the mobility the screen asks you to attack. You will save time. You will get greater stability by opening up that mobility, because that will change the balancing experience.

Why?

More proprioception provides more and probably more correct information. When walking a beam with a locked-up ankle, you’re not receiving the benefit that ankle and foot are prepared to provide. Your body unconsciously and reflexively knows how to level the pelvis and use the glutes as an advantage, not a disadvantage.

If you see people struggling, looking at their feet, flailing their arms and using unnecessary trunk movement, is this a motor control problem or a mobility problem?

My way to answer that question is if there are ‘1s’ on the FMS, get the mobility fixed first, and then attack stability. If there are ‘2s’ on the FMS, do some of these balance drills.

One question I get along these lines is about my recommendation of bear crawling to regain reciprocal balancing with better stabilization. As a matter of fact, we do bear crawling on a beam. You can determine how wide of a beam, or you can just do bear crawling on the ground.

What if you can’t do bear crawls?

Let’s all be honest here. We have clients, or recovering patients, or perhaps older golfers who because of fitness levels can’t comfortably do enough bear crawling to get the balance benefit.

Did you ever think about walking with sticks or dowels in hand? We get the reciprocal gait we get from bear crawling, without the unnecessary stress on the upper body. We get less of the unfavorable blood pressure changes people sometimes get when they get in a quadruped position.

Did you ever think about walking with sticks or dowels in hand? We get the reciprocal gait we get from bear crawling, without the unnecessary stress on the upper body. We get less of the unfavorable blood pressure changes people sometimes get when they get in a quadruped position.

Imagine watching a guy on a low balance beam who has sufficient mobility, yet has a very hard time balancing. You decide to regress, but don’t hand him one stick. Hand him two dowels and get him to do a right-left reciprocal action. Have the dowel handgrip adjusted at a nice walking height. When the left foot advances, he advances the right dowel.

Have him grab the ground with the dowel, not too far in front of the stepping foot. Make sure the dowel has a nice push so it’s complementing extension. Think about it—he’s engaging the right lat and the left glute at the same time. That’s not a bad concept, is it? That’s what we do in bear crawling, but we can do that upright without bear crawling, and the brain still benefits from the reciprocal activity.

Using sticks is a quick way to juice stability when mobility is adequate. First of all, make sure your clients use reciprocal gait with the sticks; make sure they get the rhythm down.

Put them on the beam with the sticks. Then as soon as they get confident, have them drop one or both sticks and continue on the beam. What you’ll usually see is until they start thinking about things, they’re great. The instant they start turning, walking on a balance beam and thinking about the exercise, they’ll probably falter.

It’s important to realize human balance is almost a reflexive activity. We should train it between exercises as a reset—as a stability reset. Introduce a balance beam instead of just single-leg stance exercises. It’s more functional, and it will have more carryover into other activities.

In sports where we have to shift weight with crisp precision, walking a balance beam can change the workout. Put it between sets. Use little things like mobility drills or the stick drill for certain people to juice stability. If you have a group of younger people, do a few bear crawls between each balancing activity. You’ll see crawling juice that stability as well.

Look what we did with Erwan Le Corre in Exploring Functional Movement. Watch the video, practice some drills and enjoy getting your balance!

To order Exploring Functional Movement: (DVD), (Digital)

Related Resources

-

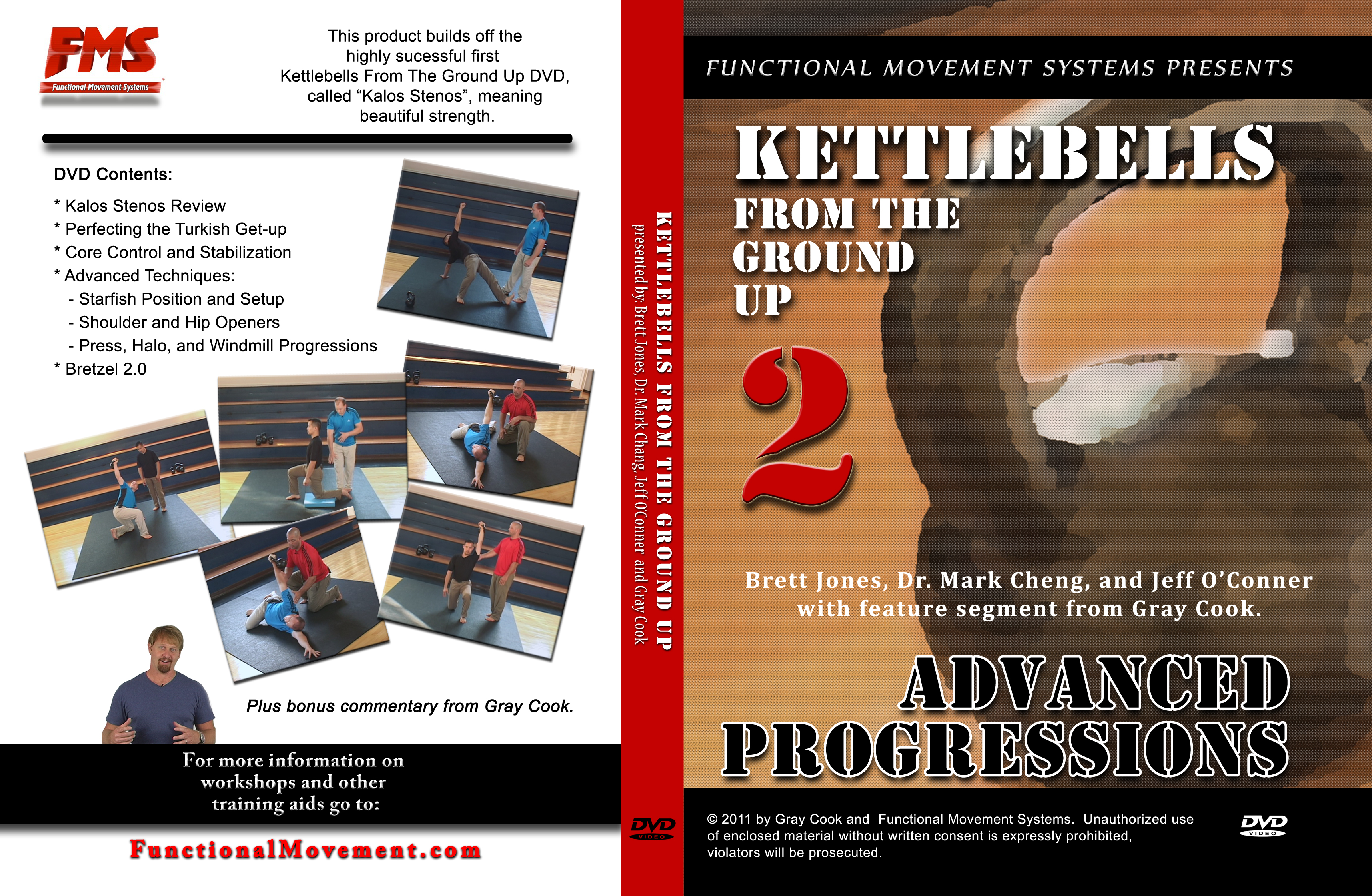

Kettlebells from the Ground Up 2

Posted by FMS

Please login to leave a comment

1 Comments

-

Dan Foley Jr 6/4/2015 5:49:23 PM

I like the tip on Standing Quadruped Movement. Especially nice placement of balance within the functional/practical context. Loving the natural blending of FMS and MovNat in helping clients improve.