Preventing Sports Injuries

Written by Byron Rohrig FMS

Sports injuries are at an all-time high. The phrase "season-ending injury" is almost as common in sports news as the postgame cliché. Many of these injuries are predictable. And preventable, say two members of the University of Evansville's physical therapy faculty

It's something educators Kyle Kiesel and Phil Plisky have been demonstrating around the globe to some heavy hitters in the sports world. And they've been making believers. But Kiesel and Plisky say they have a goal loftier than working with team physicians and in the locker rooms of European soccer clubs, the Indianapolis Colts or Chicago Bears, or the Texas Rangers or Toronto Blue Jays. Instead, they insist they'll be satisfied only when applying what they've learned and devised for assessing a player's risk of injury has become as common as after-school practices in your kid's or grandkid's middle-school or high-school program. When that happens, corrective exercises can be incorporated in a player's daily warm-ups, they say.

"What we know is your daughter may be four times more likely to be injured as the girl sitting on the bench next to her," Plisky recently told a Downtown lunchtime assembly that included parents of present and future high-school athletes.

How do they know this? They've developed an algorithm for scientifically observing bodily movements. From this, a trained observer can identify movements and balance problems which, research has shown, can make an individual a prime candidate for injury.

These musculoskeletal detectives anchor their technique in what is called the Functional Movement Screen (in 2007, Kiesel copublished a paper on injury predictions based on this in a study of NFL players) and the Y Balance Test (developed by Plisky and the subject of his 2006 doctoral dissertation when he demonstrated its predictive ability in a study of high-school athletes).

At the root of these imperfections in movement that can leave an athlete vulnerable is — very often — injury.

If someone has twisted an ankle or stubbed a toe, we typically notice a distortion in movement and say that person is "favoring" the ankle or toe. The concept in his and Kiesel's work is similar, Plisky said, except the changes they're looking for are so subtle that the human eye doesn't pick them up and the individual isn't aware of them.

Anyone who has broken an ankle knows the experience is painful.

"And pain is powerful," said Plisky. "Someone in pain moves differently. And if you move differently, you're at risk." And, even if the pain from an injury has pretty much gone away, the change in movement brought on by the injury often still is very much in play.

So here's the reason the victim of an ankle injury is a prime candidate for an ACL tear: Just because the ankle is healed and pain-free, it doesn't mean the subtle movement changes prompted by pain from the injury are gone.

Enter Kiesel and Plisky.

"Surgery fixes the hardware," Plisky said. "But our job, after that, is to work with the motor control system."

Without the latter, "It's like getting a brand new computer but running it with 20-year-old software."

Their testing is inexpensive, can be done virtually anywhere, is easily administered and translates all the research Kiesel and Plisky have amassed to practical use in assessing risk of injury. It can detect chronic ankle instability in athletes and ACL deficiency, thus identifying athletes who are at high risk for injuries to their lower extremities. It also can help determine when a sidelined athlete is ready to safely return. And, to prevent injury related to bad movement, Kiesel and Plisky prescribe corrective exercises that can be incorporated into a vulnerable athlete's daily warm-up routine to address motion deficiencies.

New discoveries from research can be added to the algorithm as they come along, Kiesel said.

Detection of injury proclivities has been blended by Kiesel and Plisky into athletes' standard pre-participation mass physical exams sponsored by Pro-Rehab, with which both men are affiliated. Pro-Rehab collects a minimal fee from players and donates it to their participating school. UE head men's soccer coach Mike Jacobs and his staff have worked with Kiesel and Plisky since Jacobs took over six years ago. Jacobs credits their program for reducing sidelining injuries on the team.

Jacobs, previously assistant coach at Duke, was no stranger to the concept when he returned to UE after serving as its assistant coach 2000-2001. Duke Medical Center is home to the "K-Lab," as the Michael W. Krzyzewski Human Performance Research Laboratory is known. Named for the school's head basketball coach, it is devoted to studying and preventing athletic injury.

"But though I found the methodology here was much like Duke's, they go into it much more indepth here," Jacobs said. Members of Jacobs' squad are tested from two to three times a year "so we have baseline data we can refer to" to evaluate injury risk of each player. Kiesel and Plisky have equipped Jacobs' training staff with exercises designed to improve flexibility and range of motion for at-risk players.

"No question we have fewer injuries now than on the team I inherited six years ago," Jacobs said. "Where it was common for players to break down, especially in the preseason, now it happens only a handful of times. It enables us to put our best players on the field the arrangement is a no-brainer for us."

The science and therapy championed by the UE professors has a reach beyond athletic teams.

For example:

Researchers in New Jersey — armed with the knowledge that kids lacking in physical coordination tend to become sedentary adults — are working with such children in grades 1 through 5 with an eye toward giving them a better chance at a healthier adulthood.

A Duke University physician is studying how to decrease the likelihood, due to movement changes, that a knee-replacement patient will eventually require a hip replacement as well.

Kiesel and Plisky, along with researchers at U.S. Army-Baylor University, are also applying the knowledge to improving the lot of the nation's warriors. They received research grants worth more than $1.5 million to perform injury-risk screening for Army soldiers, who then learn how to reduce the risk.

As recently as January, Plisky addressed the Major League Soccer Medical Symposium in Fort Lauderdale, Fla., on the subject of screening athletes and identifying at-risk players.

Related Resources

-

Movement Club

Posted by Gray Cook

-

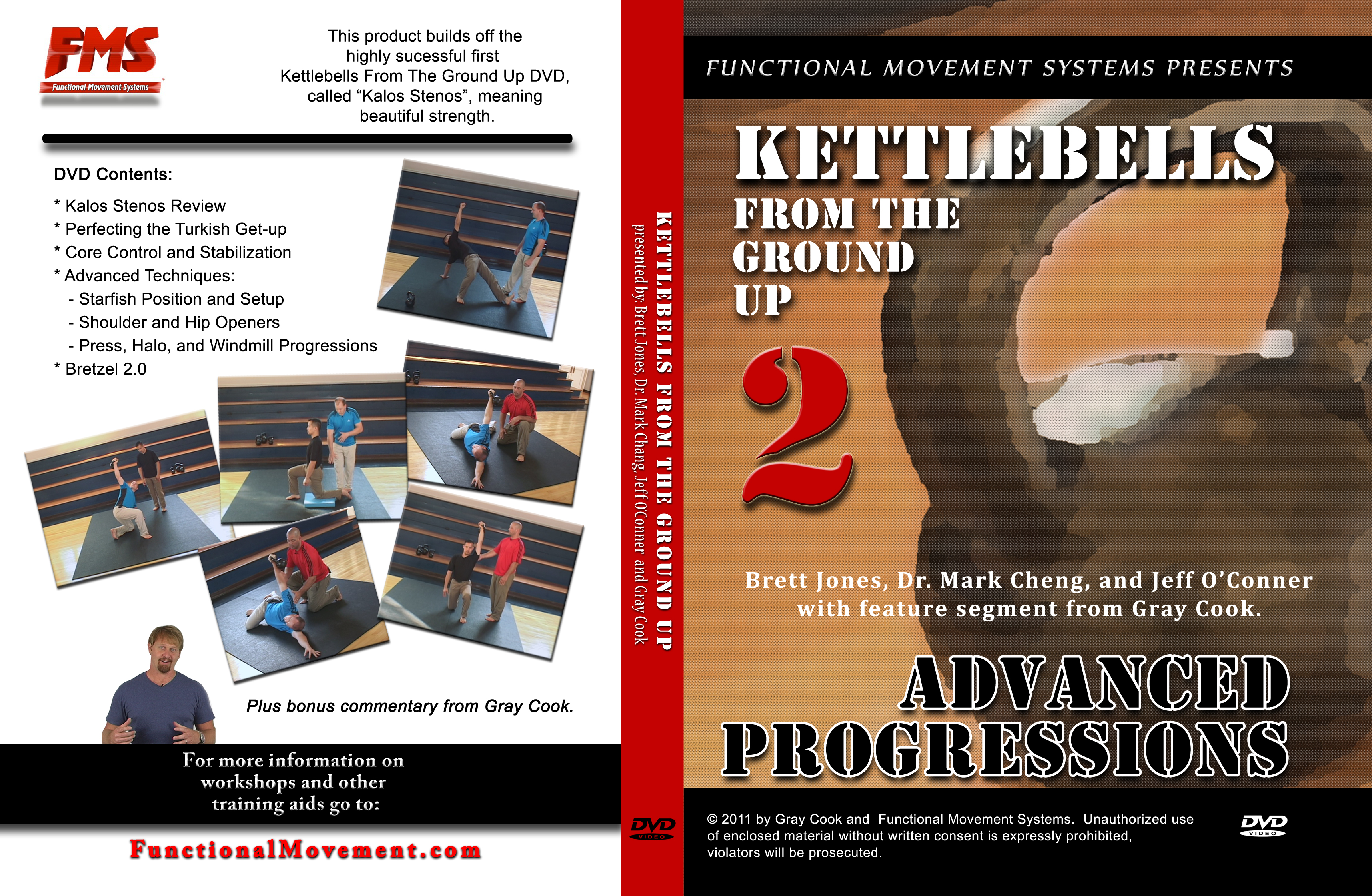

Kettlebells from the Ground Up 2

Posted by FMS

-

4 Truths About CrossFit

Posted by Lee Burton

Please login to leave a comment

2 Comments

-

Dale Macdonald 2/16/2018 8:01:14 PM

As we all know that athletes do lot of workout before starting any game, so their knowledge of regarding workout or exercise really help them to prevent from any injury. Sports Injury Chiropractor

-

christian 11/2/2016 1:24:54 PM

I think this is an interesting way of studying and trying to prevent injury. I think it is a very good way of explaining hat a previous injury can effect later on.