Whiteboard Talks: Systems Road Map

Posted by FMS

Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4

In three previous articles, I looked at a client with ankle pain, another with ankle dorsiflexion mobility limitation and another with lower quarter motor control dysfunction and deficits. These were revealed on functional screening and assessment, and the reasons it could cause, contribute to or complicate vertical jumping performance were discussed. The discussion sought to strengthen a sports science approach of removing assumptions as to deficits in performance. The central concept that supported the system of revealing such “parking brakes” to performance is known as regional interdependence, a concept central to the Functional Movement Systems. Together with altered motor control, these two concepts may be argued as being pivotal in running and jumping sports performance. Further, it has been argued that motor control may be the limiting factor in running and jumping sports performance. Esteemed sprints and jumps coach, Professor of Motor Learning, Frans Bosch, has put such an argument forward. This article continues to explore the second main reason for explaining limited performance, supporting the following question:

Let’s look at the above questions via a practical example – how to get a better vertical jump.

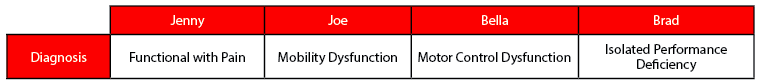

Reiterating from the first two articles, four clients entered my facility with the same performance goal – better vertical jumping performance. Jenny, Joe, Bella and Brad all play in jumping sports – volleyball and basketball. How many of you would have given them the same jumping program? Many of us would. That is until we all united around the Functional Movement Systems. Although we come from different backgrounds and methodologies, we submit to systems and logic when it aligns with science and seeks practical simplicity.

Individual athlete evaluations saw them diagnosed differently: one with pain, one with a mobility dysfunction, one with a motor control dysfunction, and one with an isolated performance deficiency.

Based on this information, how many of you would still give them the same jumping program? In sports science, we don’t like to make assumptions when possible. So, if we know what may be complicating vertical jump in each person, we can go ahead and take that assumption off the table quickly. A simple way to do that is to address pain, mobility limitations and motor control problems, then re-test their vertical jump. We will soon see the effect, or not, of movement problems on their vertical jump.

In this final part of the four-part series, I look at Brad:

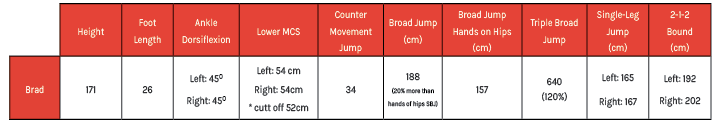

Brad had no 0’s or 1’s on the FMS, passed the lower and upper body motor control screen and displayed symmetry. His vertical jump test is underwhelming at 34cm. His standing broad jump of 188cm is greater than his personal height, with a standing broad jump to height ratio of 1.1. As a guide, being able to jump 1.0 times the distance of height is a sign of capacious force production. The ratio between upper and lower body is adequate, with his upper body contributing an extra 20% to his hands-on-hips jump, as expected. His triple broad jump comparison to his SBJ indicates he stores and reuses 20% more energy on his 2nd and 3rd jump, as is considered normal. This is also seen in his 2:1:2, adding 20% more distance to his single broad jump.

Brad simply has an isolated performance deficit.

The Fundamental Capacity Screen (FCS) can identify a performance element when the functional base is intact. Brad’s movement screening is competent, so we literally found a performance element we can attack. How hard we attack it depends on how far below the cut it is. At this point, we should not be thinking about periodization and long term gains. Before we look at a better alternative to periodizing and gaining long term adaption, let’s review key concepts.

As described in article 1, an evaluation is not functional because the evaluation looks like the sport they’re training for. An evaluation is functional because it is one that reveals an ability to respond and adapt to external and internal stimuli. The ability to respond to external and internal stimuli is first demonstrated via fundamental patterns expressed with competent motor control and minimum mobility. At stimuli greater than bodyweight, such as bounding, functional is categorized as patterns expressed with competent motor control and minimum levels of capacity according to environmental minimums (norms).

Addressing functional footprint weak links takes priority over addressing performance

If no functional movement screen or fundamental capacity screen is done, it’s very easy to see how someone can wind up at speed or jump camp as opposed to performance training that addresses their functional footprint weak links affecting their performance.

So, we don’t address dysfunctions at the baseline of their function because of their vertical jumping goal – they all have the same goal. The goal does not influence all the many distributions of outcomes they can have. Even though there can more than those four outcomes described above, you can see that those four – pain, mobility, motor control and performance – are more important than the task. The subject matter – the person – is more important than the goal. The goal of jumping higher explains to us that they’ve been having trouble jumping as high as they want. However, training for this goal by programming jumping is not the priority for the person who hurts, can’t move or leaks energy on motor control tests. If they are hurting and can’t move, they are a patient, not a well-functioning athlete with a deficient vertical jump.

We now see that we can confidently say that the whole Functional Movement Systems:

With someone like Brad, we should be thinking about “shaking the system” so we get a quick response. Let’s explore that last statement further.

When we receive someone like Brad who has an adequate functional movement foundation but demonstrates significant performance related deficits, we follow the rules of addressing neuromuscular patterning deficiencies – that is the essence of SFMA level 2 courses supported by FMS level 2 and the FCS correctives element. At the very least, and first, we look back through their programming – there’s a good chance their priorities are out of order and/or their training cycles aren’t focused on their weakest link. Focusing on their weakest link will bring quick responses. We find that weak link with a functional baseline.

Let me answer this in a practical way. When I was asked to help China Women’s Volleyball, I asked a question to head coach Jenny Lang Ping, “What are the critical factors for success that you think I can help you with?”

Coach Lang Ping’s answer was, “Our girls need more power and speed.”

How I approached the enhancement of power and speed performance was dependent on another question, “where are they now?” in relation to power and speed.

To support the adaptation plan I had to work on addressing as many pains, mobility and motor control dysfunctions as possible, to cause responses that improved the athlete’s readiness to adapt. How I practically made this work was to come up with a program that honored quick response towards adaptation. Working closely with Performance Coach Rett Larson, we managed to do the necessary pain and dysfunction-removing activities before training, during movement preparation or as a superset during training. In that circumstance, in world cup volleyball in a country that valued voluminous training, it was not a usual methodology but it honoured a system. Success might have been achieved using a different hierarchy in a western country. To be able to correct whilst in-season (usually an off-season strategy) in such a voluminous training culture is demonstrative of the importance of systematically addressing fundamental elements that support success. This case study, as it pertains to bulletproofing this specific team, has been discussed in an article elsewhere (Dea, 2015).

In the above circumstance, I was judged on performance results. Typically, an adaptation program would be implemented, built on an assumption that the athlete is ready to receive the stimulus, and thus adapt. When evaluation revealed pain and dysfunction, Coach Larson and I could no longer have any assumptions about readiness to adapt. By addressing pain, mobility and motor control dysfunctions, we could reveal enhanced responsiveness. The plan to address the head coach’s goal was “response before adaptation” – leading to enhanced performance, with adaptability and durability. In any environment, enhanced durability amongst game-winners matters.

So, we arrive at an important consideration. It relates to whether a client is paying you to entertain them with vertical jumping workouts or whether they are paying you to achieve a goal. Surely both require that the subject matter is more important than the task. We need to provide our clients with something they consider to be valuable, because it’s our business, but we also need to demonstrate we “moved the needle” – that we got a response – that we removed hindrances to advancement – since that allows us to stand up and demonstrate we are the kind of professional we wanted to be when we entered the industry.

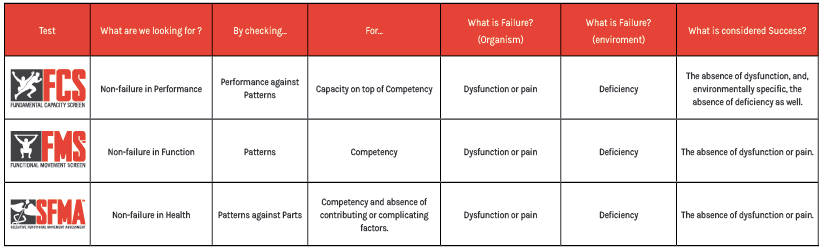

Moving the needle starts with finding out what category our client is in. This means, where is the needle starting from? For that, we use evaluations that reveal what category they are in. That category may associate with performance, function or health. A screen is a battery of measurements that first places you in a category that has a checklist manifesto running concurrent with that category. In simpler words, a screen tells us whether to systematically assess health, improve function to a minimum level, or test performance. When we test, there is a distribution or range of performance – everything from failure to the best we’ve ever seen. Within the test are confirmations that help you decide if the category is right. Assessment can still tell us about disability or pain.

If we only do the movement screen (FMS), we’re only looking at patterns. When we do the movement assessment (SFMA), we take those patterns that are painful or outside acceptable and break them down to their component parts to find out why the patterns aren’t acceptable or are painful. When we do the capacity screen (FCS), we’re taking competent patterns and evaluating capacity of performance. Then, our overall objective is to find out whether our client has a broken pattern that will be amplified by a performance task, or whether they have an isolated performance deficiency free of any pattern issue.

We’re looking for non-failure in each category.

A modern coach or clinician, working on a performance problem, should understand the five C’s – causative, contributing or complicating factors of pain, mobility and motor control, competency of patterns of movement and capacity of patterned movement. It is these C’s that direct intervention to maximise outputs. It is the first three C’s, “causative, contributing or complicating factors”, as they apply to motor control, that permits the SFMA and FMS professional to apply evaluation of regional interdependence, linking health and function across to the performance world.

It is thus easy to see that a simple performance capacity test reveals only the athletes most basic neuromuscular performance attributes. We should now understand that the test does not reveal whether the capacity deficit is due to ill health, mobility limitations or asymmetries, motor control or stability dysfunction or deficient performance capacity, until it has been evaluated to reveal the weak links.

Performance is therefore supported by competent patterns requiring healthy mobility, stability/motor control of parts – this is regional interdependence at work in the performance pathway.

We look for non-failure in each category, but what is considered success in the functional evaluations?

Success in functional evaluations requires two components. First, success in functional evaluations requires the absence of dysfunction – just don’t have pain or significant limitations in mobility or motor control in fundamental movement patterns. However, within specific environments, moving competently may not be enough to succeed. Moving competently might still be deficient to succeed in that environment. As such, there’s a second requirement for success in functional evaluations – the absence of deficiency. For example, we’ve found that the demands of the NFL don’t like those who can’t dissociate upper and lower body with a lower center of gravity. Not having a scored pair of 3’s in the in-line lunge means you are disadvantaged compared to those who do, in the NFL. In another example, in elite track and field athletics, a score of 3 in a deep squat as per the FMS criteria is associated with those who do better in the following 12 months (Chapman et al., 2013). These environments reveal that success requires an absence of deficiency, as well as dysfunction. The clear map that we use that helps those who are lost is to ask, “Are you dealing with a dysfunction or a deficiency?” If you find a deficiency, what you’re saying is that you have a normally functioning individual that you should stress them in the right environment, allocating a need to do better – even then you’re going to have response indicators.

With a 3 in the lunge or squat, the intrinsic criteria that earned you a 3 offers you a buffer zone if you need it, in the presence of fatigue or travel. This criteria is no pain, minimum levels of mobility and motor control. Having these critieria is not a guarantee of insurance, but it’s more than a 1 or 2 has. Many times, in sports you’re called upon to adapt or micro-adapt to certain weather conditions, surfaces or other issues – extrinsic factors. The more scores of 3 you have, the more room you have for sensory input. You have a higher range of a sensory gauge – if your speedometer only goes up so far, then everything after that is a red line to your CNS. If your speedometer is stretched out before you red line, you get better sensory information. So, you can look at scores of 3 in two ways – a biomechanical buffer zone or insurance policy, but it’s also a neurophysiological openness. Having scores of 0 or 1 in the FMS means you’re pre-loaded with altered motor control due to pain, or pre-loaded for movement. This is where dysfunctional compensation may likely occur as well, increasing the risk of injury. Being pre-loaded for movement means you must use more resources than others, making it more difficult to still be present at the end of a period of time. The presence of a buffer zone and neurological openness supports completing more of the planned training program, an important factor in success in performance training (Raysmith and Drew, 2016).

The recent addition of the motor control screens has bridged across from the functional patterns to capacity. Once we have an FMS or SFMA in the bag, the motor control screens are a great feedback loop to see if you believe your own hypotheses. We know that you can approach an intervention strategy like so:

Applying the above example intervention, if you’ve got a forward reach motor control screen in the bag and you pick up 3 inches of forward reach without practicing the test, nobody can deny that we levelled the system. We changed performance without going right to single leg stance, even though we’ll probably lose those 3 inches by a visit 48 hours from now. As an aside, getting that system-levelling-response towards adaptation requires a consistent monitoring of the forward reach and application of correctives for several days. This signals to the nervous system to lay down new tissue to adapt to the stimulus we’re applying.

To get that improved motor control screen, we didn’t re-pattern them at all. We didn’t even teach them to balance on one leg. If anything, we broke a faulty pattern. That’s quite different. You’ve already got a single leg stance programmed, since the first few years of your life. It’s just that your energy expenditure or attention to incoming sensory detail is completely different – you’ve just got your parking brake on – pain, mobility or motor control dysfunctions.

We are now in a situation where we must evaluate our performance trajectory to move the needle. Many professionals are used to programming out a plan, then waiting for the adaptation at some point down the track. The clear map that we use helps those who are lost by asking, “Are you dealing with a dysfunction or a deficiency?”If you find a deficiency, what you’re saying is that you have a normally functioning individual that you should stress them in the right environment, allocating a need to do better – even then you’re going to have response indicators. What we’re talking about in this example is that a performance coach will deal with dysfunctions leading to deficiencies every day without realising it. They are seeing deficient performance that is amplified from functional problems. So, when we are trying to change simple things like the forward reach on motor control screens, or leg raise, or shoulder mobility, or lunge stability and cleanness, these aren’t things we weight train for. We don’t have to wait for the allocation of specialised tissue – we can see our simple interventions manifest as a short term response that tells us we are on the right performance trajectory. We want to change these simple things so they aren’t amplified in performance tests. So, our question comes back to, “Is this person normal and waiting to become super normal, like Brad, or is this person below the cut and desperately needing to get their vital signs in check, like Jenny, Joe and Bella?” If the latter is the case, then time is of the essence and we should realise that we can see responses very quickly. Within the first or second set, we will see if we’re making motor control worse, better or the same. A person whose motor control is getting worse in the first or second set will not be due to fatigue, but a poor intervention as it relates to their dysfunction.

Whilst we make mistakes every day in addressing weak links, when we don’t see a response we don’t continue down that pathway assuming the right adaptation will occur. When using the FMS, SFMA and FCS, we have feedback loops that are both systematic and self-refining since they honour our working definition of “function” - the ability to respond and then adapt to internal or external stimuli.

So, we base a lot of our trajectory on how we are going to treat, our care plan, on those first couple of sessions. The alternative is to be very comfortable lining up multiple sessions based on an assumption and then finding out we should have done something else. It’s not necessary. It’s what happens often but it isn’t necessary. We don’t have to shoot multiple bullets to know we aren’t hitting a target if we have a good scope.

If we can’t show two to three sessions with positive responses, telling the client to be patient and wait for adaptations is breaking the rules of training. Rarely will adaptation occur without some obvious temporary responses showing themselves. For example, the first few times a client goes from a 1 to a 2 on the active straight leg raise, it will show up after the session. When they then come into a session, with a cold “2” leg raise, without any warm up or preparation, that’s when a subtle adaptation has occurred. Once an individual is strong in a single leg dead lift, we are sure an adaptation has occurred. There are a lot of people discounting the response as being “only temporary” – stringing together a series of temporary responses will see repeated signals to allocate a new or stronger-revived motor pattern as well as allocating new tissue across the musculotendinous junction.

When attempting to move the needle, if you have two different techniques that both offer some degree of success, how do you decide between the two? The answer should be “which one gets them to independence quicker, and which one is most sustainable”. Anything outside of that is more self-serving for our revenue stream than it is their independence (and performance). It should be serving the original question at history taking, which is “how can I help you?” This is sometimes more directly asked as “what is your goal?”

I return to my initial statement during the preface: “It has been argued that motor control may indeed be the limiting factor in running and jumping sports performance.” When we collectively look back on jumping performance, before we make conclusions about how to address jumping performance deficiency, we should not assume the individual has fundamental movement competence to support expressions of force production in the vertical direction. The process of revealing fundamental movement competence involves using a movement screen (FMS), then capacity of movement using a capacity screen (FCS). The evaluation revealed four different diagnoses. Each diagnosis is a different starting point. The hierarchy of competency before capacity (moving well before moving often) creates a priority list of what needs intervening to remove handbrakes to jump performance. Thus, we see how the regional interdependence of mobility, stability and motor control support positions, patterns and power. The SFMA and FMS professional can carry the concept of regional interdependence through to the FCS, or to specific capacity testing and sports performance.

Greg Dea

Performance Sports Physiotherapist

CHAPMAN, R. F., LAYMON, A. S. & ARNOLD, T. 2013. Functional Movement Scores and Longitudinal Performance Outcomes in Elite Track and Field Athletes. Int J Sports Physiol Perform.

DEA, G. 2015. Bulletproofing the volleyball shoulder. https://www.otpbooks.com/bulletproofing-volleyball-shoulder/

HOOGENBOOM, B. J. & VOIGHT, M. L. 2015. Rolling Revisited: Using Rolling to Assess and Treat Neuromuscular Control and Coordination of the Core and Extremities of Athletes. Int J Sports Phys Ther, 10, 787-802.

HOOGENBOOM, B. J., VOIGHT, M. L., COOK, G. & GILL, L. 2009. Using rolling to develop neuromuscular control and coordination of the core and extremities of athletes. N Am J Sports Phys Ther, 4, 70-82.

RAYSMITH, B. P. & DREW, M. K. 2016. Performance success or failure is influenced by weeks lost to injury and illness in elite Australian track and field athletes: A 5-year prospective study. J Sci Med Sport, 19, 778-83.

Posted by FMS

Posted by Gray Cook