It’s All About Motor Control

Written by Gray Cook FMS

A key component of motor control is muscle tone, and I want to specifically discuss inappropriate muscle tone.

Very often, from the perspectives of physical therapy and rehabilitation, we don’t necessarily see just tightness or weakness.

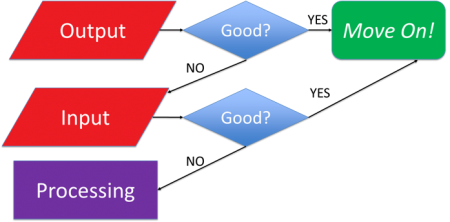

Tightness is often a way that the body uses parking brakes in the absence of real, authentic braking systems. The braking system that the body has is called motor control and it is finely tuned to input, processing and appropriate output. When a fault is present somewhere in that system—somewhere in movement, somewhere in that coordination, timing and symmetry—a dysfunction is observable.

The body is set up to survive and in a situation where the original operation is compromised, it simply creates a parking brake system—one that tends to stay engaged, slow you down and keep you out of trouble. This parking brake is a fail-safe in fatigue, injury, protection of other structures and avoidance of pain. You may have improved control, but you also waste energy and lose efficiency. The weakness issue remains evident. It is often deconditioning; it’s body-wide and not isolated and it’s easily fixed by getting up and moving today . . . and then moving a little more tomorrow. However, isolated weakness is rarely just weakness.

Isolated inhibition of a single muscle or group of muscles is best diagnosed in rehabilitation as a neurological problem or impairment resulting from injury, disease or dysfunction. The subtle and background inhibition I’m speaking of is the inability for a muscle to take a command to an appropriate level of tone to execute a posture or a pattern. Our real problem here is when we simply discuss tightness or weakness of a muscle, we can go down the rabbit hole thinking it’s a muscle problem. Very often, it’s a command problem.

If there is tissue tightening, everything from deep fascia to superficial scarring or scar tissue from a previous injury, the muscles will be told to tighten prematurely or even maintain a significant amount of resting tone simply to protect the kink in the system. This tightness can also be preserved not from a signal from other tissues but it can be left over from a previous injury that has already been resolved. The muscles never got the memo.

Imagine the child who, having broken a leg bone, graduates physical therapy with full range of motion, full strength, and even a fairly good movement screen, yet continues to limp when walking fast or running. Why? Because it’s a habit. The input is correct, but now the habitual lifestyle burdened with pain and rehabilitation has created a limp that is actually the problem in itself. A new dysfunctional pattern is in place. A limp is functional following an injury because it offloads stress and maintains some degree of mobility. It becomes dysfunctional when there is no longer a reason to offload stress—when the problem causing the limp has been resolved.

The injury that caused the limp is gone and yet the limp remains—that’s a processing problem. Inappropriate input from unnecessary tightness, poor joint mobility or poor tissue extensibility can actually cause protective tone, which we see as tightness. Even when those compensations are gone, the habit of protecting can still remain.

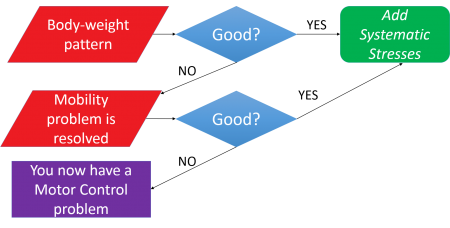

The best way to deal with increased tone when flexibility and mobility are in question is to look at the pattern. Within the pattern is the answer. It shows us all of the other issues that we’re not thinking of that could be driving the mobility or flexibility problem.

Likewise, the weakness that we challenge with strength and exercise routines, loads and movement pattern development may often be inhibition. Inhibition doesn’t reset itself very well. When we have a choice to reset our own system or simply compensate, we often compensate.

Corrective exercise is a methodology that understands the biological need to compensate and removes the opportunities to compensate, usually by exploiting regressive developmental patterns. Rather than doing everything on a functional foot position, we go back through those patterns and postures that got us standing in the first place—rolling, crawling, kneeling, tall kneeling, quadruped. We add action to demonstrate that the posture and patterns at every level support the progression to the next level.

These patterns can actually magnify the problem before we get to our feet, where compensation is our only opportunity. We can often measure flexibility problems locally and even measure strength problems locally, but ultimately, we must understand that there’s a motor control system driving this.

That motor control system is dealing with input, processing and output. Believe it or not, the easiest way to check is to simply look at output. If a movement pattern is at an acceptable level of quality, start loading and stressing that pattern to uncover the physical resources available in that particular movement pattern, shape and posture.

If a movement pattern is broken, we must go down the rabbit hole and dissect out that movement pattern understanding. Is there a mobility problem driving poor input? Or a processing problem allocating poor stability and motor control?

We can find, treat and correct these problems. We can manage these problems, not by looking at muscle, but by looking at the patterns (or the lack thereof) driving inappropriate muscle tone. Remember, tightness and weakness represent the same problem, just at both ends of the spectrum.

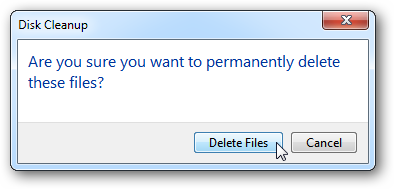

Too much unnecessary muscle tone looks, on the surface, like poor mobility and must be managed. Is something driving it or is it simply a habit that is stuck on a hard drive that could use cleaning?

Is the weakness actually something that just needs sets and reps or is the weakness driven by inappropriate mobility, motor control or inefficient patterning causing compensation?

Is the weakness actually something that just needs sets and reps or is the weakness driven by inappropriate mobility, motor control or inefficient patterning causing compensation?

Is that compensation due to a lack of mobility or motor control somewhere else in the body that has gone undetected for years or is it simply something on the hard drive that just needs to be scrubbed off?

To easily find these issues, we need systems. But as long as we insist on talking about local muscle tightness or weakness, we will miss it. It has often been said that the finger pointing at the moon is designed to show you the moon . . . most people just see the finger.

Inappropriate muscle tone is a symbol representing disharmony in the system. The disharmony can either be due to an input problem being appropriately processed or appropriate input being inappropriately processed.

We need to approach it in this clean and systematic way so we can find out which is driving, because it is not always clear otherwise. The clichéd answer is that inappropriate input and inappropriate processing is likely what’s going on in every situation.

That may be true to some degree, but now your action points are spread out and you do not have a feedback loop for your intervention. If, on the other hand, you think that somebody’s poor motor control in their hip is due to a lack of ankle mobility, you can simply answer that question without even going onto social media. Create a little more mobility in the ankle and then recheck hip motor control. If the ankle mobility problem was creating poor input and driving the bad motor control and general weakness in the hip, then you’ll have your answer. If it wasn’t, you’ll also have your answer.

This deductive reasoning is the ‘source code’ behind Functional Movement Systems. If you want to know whether it’s a mobility or motor control problem, do the test. That’s why we built it—for us. We had the same questions and could not find a tight system with logical answers. We didn’t set out to develop a screen or a system . . . we just wanted a competitive advantage. If you want to find out what’s driving the inappropriate tone, we have some assessments that will do that very well. If you want to measure motor control with an unbelievably efficient and functional test, we have that too.

This deductive reasoning is the ‘source code’ behind Functional Movement Systems. If you want to know whether it’s a mobility or motor control problem, do the test. That’s why we built it—for us. We had the same questions and could not find a tight system with logical answers. We didn’t set out to develop a screen or a system . . . we just wanted a competitive advantage. If you want to find out what’s driving the inappropriate tone, we have some assessments that will do that very well. If you want to measure motor control with an unbelievably efficient and functional test, we have that too.

We try to embrace movement metrics in a way that helps you have tighter feedback loops—to know whether you need to focus on individual correctives or programming modifications.

At any given time, one of those moves will make the biggest difference. Understanding in a biological system which is broken—the organism or the environment—is the hallmark of good science, and tracking movement behavior is where this starts in exercise and rehabilitation.

We’re Functional Movement Systems. We’re not an exercise company.

We offer better tools to look at movement and to create feedback for the individuals who depend on you for programming, rehabilitation and specialized performance training. It is true that movement screening, testing and assessment take time. No apologies there, as we should all take more time developing an action plan. That time spent in evaluation saves experimental time in rehabilitation, movement correction and physical development.

It’s the old Carpenter’s Rule: Measure twice and cut once.

When a new measuring stick is introduced and appropriately vetted, there are only two reasons why one would not adopt a tighter feedback loop into their professional practice:

- They don’t have faith in the new tool. More articles and posts won’t give them that faith...they need to put it in action.

- They don’t have faith that their methods can positively influence the baseline. Isn’t that the challenge we all face.

Related Resources

-

The Value of Self-Limiting Exercise

Posted by Gray Cook

Please login to leave a comment

5 Comments

-

Mike 8/22/2015 12:21:46 PM

I love these articles and it's almost like there is a underlying common sense behind it all.

But I have read a few and I have never been able to find what a correct movement pattern is, for example what is the correct movement pattern for a squat?For me I feel if I knew what people where surposed to be doing I could then spot an incorrect movement pattern better.Can anyone help?Mike@bodyism.com -

Bryan Quigley 8/23/2015 11:23:10 PM

Great read! Thanks, Gray!

Mike, have you read Gray's book: Movement?

-

Balanced Athlete 8/28/2015 5:32:05 PM

Great article Gray. Finger pointing at the moon is old Buddhist expression.

-

-

Lisa 9/10/2015 8:00:33 PM

Excellent article Gray! It really helps me to think about how I want to approach a patient. I took the SFMA and FMS courses 2 years ago and the information has been invaluable! Thank you!

Six of my coworkers will be taking the class in November in San Francisco. I'm so excited to be able to talk shop with them after the class.