Using the "Reset, Reinforce, Reload" Strategy to Rehab China's Volleyball Team

Written by Greg Dea SFMA

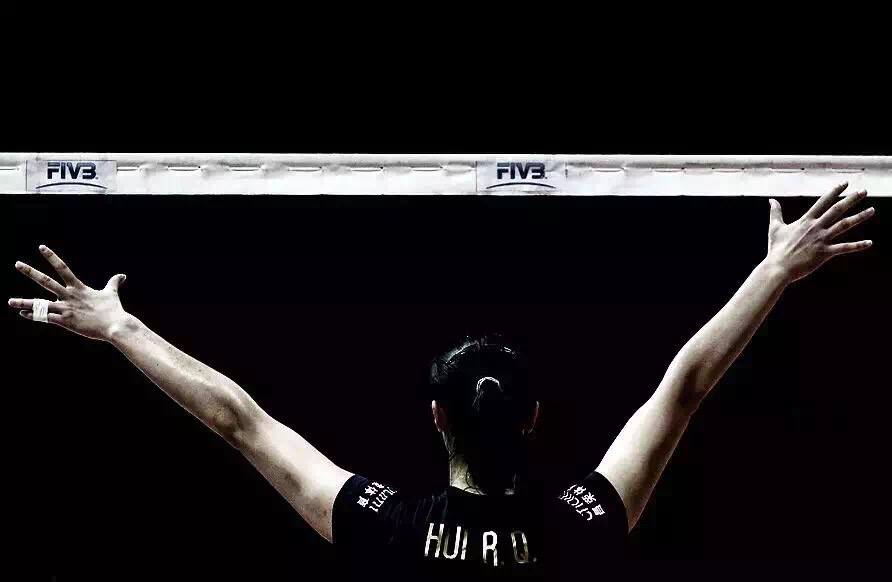

In the lead-up to the 2015 FIVB Women’s Volleyball World Cup, seven key contributors on the Chinese Women’s National Team were experiencing significant pain in the shoulder of their hitting arm.

When the problem first arose, Coach Lang Ping was confused as to what was causing the shoulder pain in her players. She hadn’t changed her training regimen and had never experienced shoulder pain similar to her players.

In this article, we will share the system FMS Lead Instructor Greg Dea employed to diagnose and treat the shoulder problems, eventually helping the Chinese team to a Gold Medal in the World Cup.

As the peak in training approached, the aim to squeeze a little more stimulus into the shoulder strength exercises led to the athletes chasing a subtle increase in isometric hang time. This led to players developing active trigger points in their shoulder adductors. The two isometric hang time exercises which provided the most problems were 1) a sustained hold chin up and 2) Bruce Lee’s Dragon Flag. The effect of these two time-under-tension exercises on key on-court movements was obvious – difficulty with overhead movements. The service and hitting action suffered. Let’s look at the action, described in a post Dea did for On Target Publications:

There are two elements of hitting and float serving that are highly stressful on the shoulder and contribute to shoulder injuries in volleyball athletes:

-

The ratchet style follow-through;

-

The absent follow-through.

The ratchet style follow-through

The ratchet style follow-through occurs when the arm follows through on the same side of the body.

In most throwing sports, the follow-through involves rotation through the trunk and pelvic girdle. In the ratchet style follow-through, this doesn’t happen—leaving deceleration mechanics to occur almost exclusively at the shoulder girdle.

In the ratchet style of hitting and serving in volleyball, once you remove the rotation across the body, you remove deceleration through the trunk and pelvic girdle. This means all the deceleration occurs at the shoulder girdle and glenohumeral joint. This places fast and high strain on the muscle groups and their connective tissues that decelerate scapula anterior tilt and protraction and glenohumeral joint extension and internal rotation; for example, supraspinatus, infraspinatus, middle and lower trapezius. It also places fast and high strain on the long head of biceps tendon and it’s attachment at the glenohumeral joint labrum. Remember what we know about rotator cuff and labrum injuries: they may become non-painful, but they don’t heal back to normal.

The absent follow-through

The absent follow-through happens in a float serve where the athlete’s hand finishes its movement very soon after hitting the ball. It is a stunted follow-

through to minimize spin. It can also happen when a middle blocker pulls their hit at the net to prevent net contact. This places high stress on the muscle groups that decelerate glenohumeral joint horizontal flexion, adduction and internal rotation and scapula protraction and anterior tilt; for example, middle and lower trapezius, infraspinatus and posterior deltoid.

Both of these actions contribute to the increased likelihood of injury to the rotator cuff tendon, labrum and suprascapula nerve. These actions also contribute to fatigue-derived inhibition of the above muscles.

We don’t want to stop athletes from performing these two actions. We want to offset the effects of them through off-court training.

After identifying the types of sport-specific movements that were causing shoulder pain in the seven players, Dea took the following approach to fixing it.

- Go looking for your “handbrake”

- Improve your mobility

- Add “underbelly” movements

- Add movement skills

RESET

Firstly, Dea looked for the “handbrake” by using the SFMA and FMS. The goal of this was to find movement patterns that were causing resistance in mobility that supports high arm swing speed.

Having movement through all patterns, without pain is so important to provide the nervous system with the feedback it needs from all positions of the upper limb, uninterrupted by pain, to maximize motor (movement) control. If that’s the case, we know that the joints can get into particular positions and can control those positions. This is the essence of mobility underpinning static motor control or stability around the appropriate joints. This gives the appropriate joints opportunity to use the now pain-uninterrupted nervous system to respond, reflexively, to perturbations.

Dea started with improving shoulder adductor muscle extensibility and thoracic extension because swing patterns require full shoulder flexion and abduction with proper thoracic extension and rotation mobility or else that requirement for mobility will be passed on to the glenohumeral joint and lumbar spine. Because of this, without the proper mobility in the shoulder adductors thoracic spine, pain and dysfunction will be felt in the soft tissue and joints of the glenohumeral and thoracolumbar junction area.

After figuring out the “handbrake” – shoulder muscle adductors and thoracic spine mobility – Dea began treating trigger points and improving mobility.

Here’s a sampling of exercises that Dea employed.

REINFORCE

After improving mobility to support high swing speeds, Dea then looked at adding “underbelly” movements in order to improve motor control and stability to support high arm swing speed. “Underbelly” movements often referred to as “reflex activity”, occur in movement patterns without our knowledge.

Here’s the punch—reflex activity drives stability, both statically and dynamically. An example of static stability is when one body part is not moving, but the body moves around it. An example of dynamic stability is when the body is not moving but the body part is moving around it. Both of these variations require control of movement, i.e. motor control.

Dea incorporated the supine arm bar, side-lying arm bar the Turkish Get Up and variations of these exercises to restore stability and motor control to the shoulders of his athletes.

These exercises serve to subconsciously reinforce correct movement patterns through improving motor control and stability.

RELOAD

After resetting movement patterns and reinforcing corrected patterns, an athlete is prepared to move onto the reload process. In the case of volleyball athletes, reloading involves offsetting high volume sports-specific movement patterns by training movements in the opposite direction as skills of sport.

As Dea says, “the exercise doesn’t need to look like the hitting position. It only needs to provide an opportunity to reinforce the pattern opposite to the hit.”

A few of the exercises Dea used included:

All seven players returned to top form in time for the 2015 FIVB Volleyball Women’s World Cup. China won the Gold Medal.

“Volleyball athletes are not shoulder athletes. They are whole body athletes who suffer shoulder, low back and knee injuries,” Dea says.

Volleyball athletes can’t afford to avoid techniques like the ratchet and absent follow-through, but they can’t afford to suffer from them either. Athletic preparation needs to involve resetting movement patterns correctively, reinforcing those correct patterns, and offsetting sport specific movements with opposite movement patterns.