Strength?

Written by Gray Cook FMS Pod Casts

Looking back over the Essentials of Coaching and Training Functional Continuums DVD I did with Dan John and Lee Burton, I realized how often we mentioned strength.

This could potentially be the most polarizing topic that I’ve ever approached, only because I feel that many will think I’m saying strength isn’t important.

I’m not.

I’m saying that the word strength does not have the level of communication and accountability that it should.

When a term as valuable to physical development as strength lacks clarity, vital signs and standards, it ceases to be actionable. It becomes something that every group discusses, but that each values differently. If strength is fundamental, then why can’t we have a normal value as with vision (20/20) or blood pressure (120/80). Why is it so hard?

It’s hard because we want to discuss specific strength before general strength—a short-sighted and unsustainable outlook. The foundation for long-term specific strength is a solid, general base.

When we look at words like strength or flexibility, they can be applied to a person in reference to will-power or your adaptability, or they can be applied to a physical attribute. For the purposes of this article, we’re definitely talking about the physical attribute of strength. Having said that, I’ve got a love-hate relationship with that word.

When you hear the word strength, do you think of lifting or do you think of work capacity? Be honest with yourself.

For a large portion of my life, I’ve thought of strength as lifting. But that wasn’t always the case.

Growing up in a rural community, I thought of strength as the ability to work. Then, I was introduced to the weight room in high school and college, and I thought strength was lifting. Now as a professional with a quarter-century of education, mistakes and meditation on the subject . . . I’m back to thinking that strength is the ability to work.

If you’re in a lifting sport (power lifting or Olympic style weight lifting), then I think you have to focus on lifting. If you’re in a sport that prizes work capacity, then lifts are not necessarily the only way to generate strength. They are, however a very important way to generate strength in patterns when it’s appropriate. Two questions must be addressed by the strength professional in a non-lifting sport:

What’s the vital pattern to be strengthened?

What’s the minimum effective dose to get there?

When I use the phrase work capacity, I could basically shop that term from the tactical athlete, to the senior golfer and even to the 10-year-old gymnast. Work capacity is the integrity of postures and patterns against fatigue across time. Every athlete or every enthusiast in a physical hobby has had to confront the point where their fatigue reduces their technical precision and skill development.

Let me simplify work capacity. If we’re talking about repetitions:

Any repetition with integrity should get you an A or a B on the qualitative strength-grading scale. Any repetition without integrity should get you a D or an F on the strength scale. If you can’t decide on integrity, you’re forever stuck at a C.

How many imperfect reps do you have time to do today? If you don’t have an integrity gauge or a quantity-against-quality gauge, you will never be able to truly value work capacity. You can quote me on that.

We want to strengthen athletes and active people so they can pursue the activities they want and develop the skills they want. You can’t pursue skill development—activities that require physical capacity or movement complexity—if you don’t have a general or basic resistance to fatigue. Once you start to fatigue, your proprioception, your concentration, your flow, your respiration and your physiology start to suffer. Everything suffers with fatigue.

That suffering state is a bad platform for practice. I use the word practice because when we’re developing skill, it’s more about that technical precision. When we talk about training, that’s taking a minimum level of technical precision and seeing how much volume we can put on it before we cross that line in the sand—integrity.

That suffering state is a bad platform for practice. I use the word practice because when we’re developing skill, it’s more about that technical precision. When we talk about training, that’s taking a minimum level of technical precision and seeing how much volume we can put on it before we cross that line in the sand—integrity.

Don’t get me wrong. I think strength is a noble word, but we use it both so broadly and so shallowly that no single group that needs to discuss strength can agree on what it is. For lack of a better definition and in my humble appreciation of the word, strength is work capacity.

If it is work capacity, then quit calling it strength.

Strength, in my mind, is a sub-category that is integral to work capacity—probably the ability to use muscular tension to perform work or to protect space—using your muscles to protect your range of motion, your posture, the point at which you occupy space and the world around you. It’s that resistance to external forces that could damage you, knock you off balance or take you off your path. It’s also that muscular tension that allows you to perform work by moving your joints with maximum efficiency (the minimum effective dose I discussed earlier).

That work must have a certain level of integrity or it’s just wasted motion and nature does not appreciate things that aren’t economical. In the grand scheme of things, blasting out those extra five repetitions with a loss of integrity probably doesn’t get you much. You probably did more repetitions than your partner, but you crossed a line that the great ones try to never cross.

Outside of a lifting sport, what good is a lift if it can’t be valued or represented in some form other than a lift?

Somebody training, let’s say, to go into the military, heads to Parris Island to go through USMC boot camp. Believe me, I have a few buddies that went to that place and when they came back, they looked a lot different than when they left.

They all hit the weight room and they all ran hills and they all did different things to harden their body and get ready for the work ahead. However, what they went through at boot camp was more about lifting themselves and being competent with their bodyweight and that of the equipment on their backs, whether on a 10-mile hike, a 10-mile hike with a pack, or a bunch of pull-ups, push-ups or leg lifts. It didn’t matter.

Nothing in the weight room, where they got to decide how many sets, repetitions and muscle groups they would work on today, really distinguished them. The environment that they stepped into outside of that weight room was where they had to put it all together and they had to perform. If the reason you’re lifting is to create work capacity for something that is going to be valued outside of the weight room, never let your lifting schedule interrupt your development of work capacity.

One of the things that I chuckle about (maybe you do as well), is when I ask people, “Give me a representation of your strength?” They’ll all tell you a one-rep max or a three-rep max in a lift that they did five years ago.

I hate to say it, but what I was five years ago ain’t what I am now. That’s true for most people. Strength should be reported numerically and scientifically in different valuations of work capacity because I’ve always said, “if you practice the test that we’re using to gauge you, then the test becomes obsolete as a biomarker.”

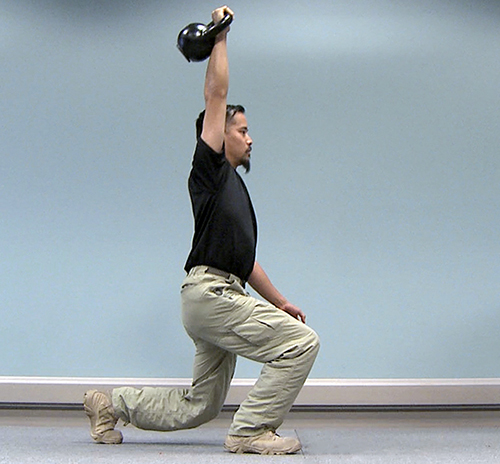

A marathon is a light-and-long representation of work capacity and a farmer’s carry with substantial weight is heavy-and-short work capacity. Both activities make you own your postures and patterns in order to have success—the postures must have integrity, the patterns must have economy.

If we started training you for SAT-type testing in the eighth grade and ran you through SAT-type testing every month of your life until you were a junior in high school, I’m not so sure that SAT would represent your success in the first year of college—which is really all it was designed to do.

The minute you practice the test and then turn around and tell somebody, “I’m strong because my deadlift is this much,” they may say, “Well, how many hills can you run?” “What does your farmer’s carry look like?” “How many pull-ups can you do?” They’re not challenging your strength. They’re challenging your narrow definition of strength.

Most universal truths cannot be communicated in words, but with the right words, they can at least be valued as a common experience by almost everyone. If we could basically take the current way we use the word strength and literally kill it, nail it to the wall and let it die, then we would start valuing work capacity, which is the reason most of us lift in the first place. When that happens, I think we could come up with a better, more usable definition of the word strength—a word that never asked to be misused in the first place.

What do you think? We’ll talk definitions in Part II.

Related Resources

-

Why We Prefer the Hardstyle Swing

Posted by Gray Cook

-

Should You Screen Kids?

Posted by Gray Cook

-

We Can't Do It Better Than Nature

Posted by Gray Cook

Please login to leave a comment

7 Comments

-

Jeff Kehler 12/17/2014 8:48:34 PM

Interesting topic Gray, love your stuff.

Aside from Personal Training, I'm also a Cycling Coach. An interesting thing in cycling is the way we define a strong athlete. Not long ago our only solution was for determining strength involved testing blood lactate to establish a "lactic threshold", and did exhaled gas tests to determine Vo2Max.

With the advances of technology virtually every pro, and many novice racers have a power meter built in to their bikes. It's basically a strain gauge, but the cycling computers also calculate your cadence (RPMs), which give you your wattage output.

To define a "strong" cyclist we measure critical time points to establish their strengths. Maximum 1hr average power, 5min average power, 1min average power, etc. We often further take the athletes weight into consideration -hills are a big part of the sport- to get their W/Kg (Watts per Kilogram of body weight) over a set period of time so that we can compare athletes predicted performance over a given terrain.

I know it doesn't transfer to the football field as easily, but I think it's a decent example of what you're referring to -

Ann Gardner 12/17/2014 8:48:36 PM

Fantastic!

This has been one of the many debated or questioned terms along with a few others. I've had discussions with other trainers and clients to find ways we can try to define - strength. By the end I found it more meaningful to apply work capacity. 1) Because it's relative, 2) it can be gauged as the work progresses/continues (is it easier, better, smoother), 3) is the work done properly, (form, posture, recovery).As mentioned the terminology can depend on POV (i.e. lifting) to which strength is often associated. I am happy to read the importance of foundational (base) to properly improve work capacity and that integrity takes precedence. It would be amazing to see if/when the physical/fitness development sector draft an unanimous and clearly defined termsto aid in educational means and the removal of mis used or mis-aligned terms.Great article, I can't wait for part II. -

Dan 12/17/2014 8:46:22 PM

I agree. The word "strength" without a qualifying action be it a squat, pull up......etc, is useless but in the rehabilitative world we use strength as compared to another body part movement still has value. I am not, and never was, a fan of the 0 to 5 strength scale but as a starting point using the comparison of injured limb to non injured gets us back to start before an assessment of "work capacity", "functional strength" can be sort after, and then a program to return to work, function, recreation. Having said this I realize a direct correlation of a particular isolated movement and ability to perform a function is not a direct correlation but it is still a start if the movement is not available.

-

-

-

Balanced Athlete 9/22/2015 7:53:13 PM

Thanks for pointing out that strength is a multidemensional word when relating to aspects of a human being--so true--old paradigm needs to be buried.

-

jim 12/22/2015 6:54:06 PM

There are "different" types of strength: Absolute, speed, repetition etc.....but only one influences and is king above all others as they all follow its lead : Absolute!!!